An art historian’s inside reaction to an art court case

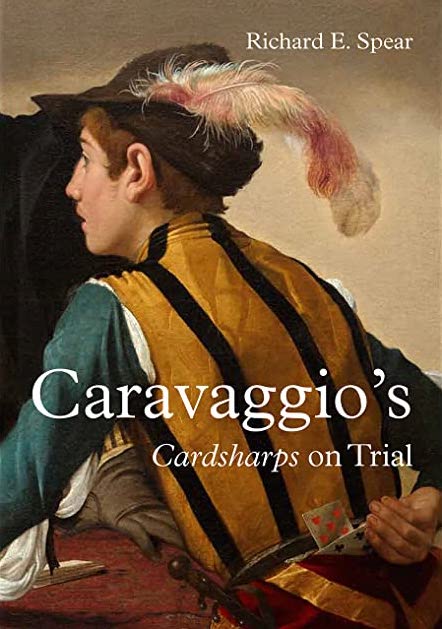

Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial

by Richard E. Spear

2020, The Burlington Press

Ever wonder what goes down in an art dispute that makes it all the way to trial? I do. Or rather I did. Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial is a dive into the deep end of what happens when the authenticity of a piece of art is at the centre of a lawsuit that doesn’t settle.

This book is, start to finish, about one case: Thwaytes v. Sotheby’s. To summarise it as quickly as possible, Sotheby’s sold what they believed to be a non-autograph copy of Caravaggio’s The Cardsharps. The pice was bought by a nonagenarian Caravaggio scholar who declared it to be real. Most experts disagreed. The ex-owner of the painting sued Sotheby’s claiming (more or less, the argument changed a few times) that Sotheby’s should have consulted an outside expert about the piece. Sotheby’s argued that they believed the painting to be a copy and, thus, didn’t warrant further research, that if there was any indication at all that it was by Caravaggio they’d have been motivated to find out, and that they still think it isn’t by him. It was all up to the court to decide.

If you are unfamiliar with the outcome of the case and are considering reading the book, why not refrain from searching for articles about it. It’s more fun to not know how a book like this is going to end. I won’t put spoilers here.

Sure, Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial, provides a detailed discussion of the background to the case, a tick tock of the trial, and the implications of the decision, but it is not from the perspective you might expect. Rather than being written by one of the lawyers on the case, as was “Landscape with Smokestacks: The Case of the Allegedly Plundered Degas“, Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial was authored by one of the expert witnesses at the trial, art historian Richard E. Spear. This is a rare exploration of a legal case from the point of view of the academic art connoisseur, meaning that instead of focusing on legal arguments and points of law, the book focuses on art historical arguments and points of science, research, and ‘the eye’. It’s a really cool angle to take, I can’t stress that enough. It makes a long book about court testimony interesting, perhaps none the least because Spear doesn’t hesitate to thoroughly dismantle the testimony he disagrees with. Even though he invites readers who have limited time on their hands to skip over the courtroom chapters, I was there for each page. I was there for the polite academic smack-downs.

But aside from my love of figuratively popping a bowl of popcorn and settling in to watch an academic art history fight play out in front of a judge, Spear’s perspective and experiences on not just this exact case, but on the role of expertise within the art world and as part of art disputes. In a case that hinges on a questions about what type of expertise Sotheby’s employees actually have and when they are obliged to seek outside connoisseurship, we have the thoughts of one of those connoisseurs in context. Spear effectively argues for a pure connoisseurship, untainted by market money, and superior to purely scientific or technical examination of art. He thinks the version of Cardsharps that Sotheby’s sold was a non-autograph copy; he thinks Sotheby’s had the expertise to tell it wasn’t a Caravaggio; in the book, he tells you why.

I warn that it is a one-sided argument against the argument of the ex-owner of the disputed Cardsharps. It is also a one-sided argument against the arguments of some of the other experts who were called for this trial. Spear quotes heavily from their testimonies, but the quotes support his own narrative. I can’t help but think the people he was quoting would disagree with how they are portrayed. That said, he supports his arguments well, and he isn’t outright mean. Gosh, he convinced me.

I don’t think that the Thwaytes Cardsharps was painted by Caravaggio.

Of course I’m not the person who needed convincing. How would a judge react to the swirly whirly world of art authenticity? Don’t google it. Read the book and find out.

I’m grateful to my colleague Lars van Vliet for letting me know that this book had come out. He sent me a WhatsApp image of his copy, and I rushed online to request a copy of my own to review here. I’m looking forward to living in a world again where I can sit with my colleagues and have scholarly chats. Lars is a lawyer and an art law expert, where as I’m much more on the fluffy art historian side of things (if I’m anything). I’ll be interested to hear his take on the book. If you read it too, do chat with me about it and we can pretend that we’re by the coffee machine or water cooler in the Faculty of Law, being normal. I’m always on the twitter…