Not quite, but this isn’t a surprise.

Earlier this month, in a report commissioned by The Mexican Museum of San Francisco, Dr. Eduardo Pérez de Heredia Puente found that out of 1,774 pre-Columbian Latin American antiquities in their collection, only 85 of them were both authentically ancient and of “museum quality”. The rest, then, were minor at best, fakes at worst. In a quote from the report cited by Lydia Chavez for Mission Local, Dr Pérez de Heredia Puente stated that among the museum’s ancient collection were “a good number of modern workshop ceramics, imitating the archaeological ones […] from bad to good copies, including some good and high-end forgeries.”

For those of us who follow the dirtier side of the market for antiquities and for archaeologists who work in Latin America [1], there’s no surprise here. The market is filled with Central and South American fakes and those fakes eventually roll into museums (and academic research). Perhaps the only notable aspect of this story is how open the Museum is being about the situation and their efforts to clean up their collection and their act.

So how did we get to a point where a museum is storing shelves and shelves of forgeries? Let’s take a look.

Faking the Ancient Americas

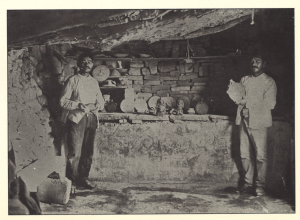

Hermanos Barrios, late 19th/early 20th century Mexican makers of imitation artefacts with fake wares on display.

Ever since the 1841 and 1843 publications of John Lloyd Stephens‘ landmark best-sellers Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán and Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, featuring Frederick Catherwood‘s sumptuous illustrations of Maya iconography [2], folks have wanted to buy pieces of the pre-Conquest past. Objects from Central and South American cultures grew in popularity through the whole of the 20th century, and this market demand inspired devastating looting which destroyed whole ancient cities and has undermined our ability to study these cultures.

Even though Latin American countries have found it difficult to combat this crime since it is entirely rooted in the external desires of wealthy foreigners, many enterprising individuals sought to meet market demand without having to locate tombs in forbidding jungles. Tourists, collectors, museums, wanted the ancient Americas, so folks made the ancient Americas. Fakes have been a feature of the pre-Columbian antiquities market since there’s been a pre-Columbian antiquities market.

And don’t just take my word for it. In 1910, Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres published the book Antigüedades Mejicanas Falsificadas: Falsificacion y Falsificadores (Fake Mexican Antiquities: Forgery and Forgers) which I have scanned for you here. To quote me on the topic: “Batres shows that faking on an almost industrial level was common well before his publication date of 1910”, documenting the astonishing amount of fakes in Mexican collections at that early date and even visiting the workshops of forgers to see how they produced their works. If the market (and museums!) were saturated with fakes then, imagine how bad the situation is now.

And don’t just take my word for it. In 1910, Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres published the book Antigüedades Mejicanas Falsificadas: Falsificacion y Falsificadores (Fake Mexican Antiquities: Forgery and Forgers) which I have scanned for you here. To quote me on the topic: “Batres shows that faking on an almost industrial level was common well before his publication date of 1910”, documenting the astonishing amount of fakes in Mexican collections at that early date and even visiting the workshops of forgers to see how they produced their works. If the market (and museums!) were saturated with fakes then, imagine how bad the situation is now.

Now I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that not all of these items were made to deceive. Many of these items were not initially sold as ancient, rather they were marketed as good (or good-enough) imitations for visitors: the kind of “tourist ware” that occupies most of the surfaces in my flat. Yet as time passes and these items change hands, Great Aunt Mabel’s souvenir of her 1922 holiday in Mexico morphs into the real deal…and enters the market and museums.

Certainly read Faking Ancient Mesoamerica and Faking the Ancient Andes by Nancy Kelker and Karen Bruhns for more info on all this.

Connection Between Looting and Fakes

Unique Mexican artefact or fake? When it appeared at a Paris auction in 2015, Mexico said fake, but how can we know for sure?

Why are fakes able to pass into museums? Why can’t we filter them all out? Because of looting! Or rather, because of a market that accepts looted artefacts rather than rejecting them outright.

In an ideal situation, a buyer or a museum would only buy or accept an artefact that can be shown to have been excavated properly and exported legally[3]. If they did this, few if any fakes could enter a collection as each piece would have a significant paper and photograph trail from ground to gallery. Any object without such provenance would be rejected, keeping the loot and the fakes out.

Yet the market accepts artefacts with little or no ownership history, provenance gaps, and a general understanding that their origins are illicit if not outright illegal; everyone knows the objects are looted because that’s where antiquities come from. This legitimisation of looted artefacts with no history creates an opportunity for forgers, and antiquities that have no paperwork because they are authentic and looted end up looking exactly like antiquities that have no paperwork because they are fake. The acceptance of one crime creates the opportunity for more crime and that has certainly not been lost on purveyors of fine pre-Columbian forgeries.

The Problem with Donations

These smiling guys, with their modern market appeal, seem to turn up curiously often in pre-Columbian foreign collections. Pic from The Mexican Museum site.

There’s another issue here: museums are growing more and more dependent on donors and those donors often saddle museums with junk. Challenging the junk or questioning the donation risks insulting a much-needed benefactor. Museums, especially small ones, end up taking in questionable objects in high pressure situations. In this case, the acting director of The Mexican Museum said that the museum was “accepting everything” and it was reported that “[t]he items reviewed in the June report came from gifts made from some 50 different donors”.

In other words, the museum was taking in all sorts of antiquities (real, fake, looted, legit) without asking any of the questions that should be asked. Great Aunt Mabel’s souvenir becomes a legitimate antiquity through the action of museum accession, and the museum potentially becomes the receiver of stolen goods. The donor feels great and, perhaps, forks over some money along with the objects and the museum ends up in the situation that The Mexican Museum is in.

Polluting the Corpus

Sadly there’s no magical or scientific way to tell if an artefact on the market or in a museum is authentic if it wasn’t properly excavated. Some tests can definitively prove a piece to be fake, but apparent authenticity can be the result of forgery techniques that are just really good. Archaeologists, then, who try to make the best out of a bad situation by studying looted antiquities in private and museum collections may actually be studying modern fakes. Thus what enters our corpus of knowledge about the ancient Americas is actually what a couple of enterprising potters in the 1960s were able to flog to unsuspecting tourists. It pollutes our understanding of the past in a way that we can’t possibly clean up (see Grolier Codex).

The headline might be “museum got duped”, but I think our real discussion should focus on what this reveals about how tainted our unprovenanced pre-Columbian collections are. At the very least scholars, museums, everyone, should stay away from Latin American artefacts that were not properly excavated for both moral and professional reasons: moral because publishing loot legitimises looting; professional because of the risk of bestowing scholarly acceptance on fakes, the sort of academic “Shaky Ground” that Elizabeth Marlowe warns against in her work on “ungrounded” Roman antiquities. Poor foundations for pre-Columbian scholarship built on foundations of loot and the fakes that looting allows in.

Archaeologist Rosemary Joyce hits the nail on the head, noting the “tension” between “objects with secure proveniences and those that, while spectacular, lack the certainty of knowledge that comes with controlled excavation”. She goes on to say that the “most disturbing is the realization that many of the securely provenienced objects included in the exhibition might be questioned because of their unique features, if they lacked archaeological context”. I agree.

Dog with bone acting exactly how modern westerners expect a dog to act. For the market or representing ancient thought? Who knows?! Photo from The Mexican Museum site.

So while I am happy to hear that The Mexican Museum is actively researching their collection, is publishing their findings, and is bringing in professional standards for acceptance of donations, I’m sad that I have to be suspicious when I walk into a museum outside of Latin America. Despite whatever expertise I have on pre-Columbian antiquities, I always wonder if everything that I’m seeing is fake, designed to appeal to tourist tastes. We want a window into the past, what we get is a window into Great Aunt Mabel’s souvenir shack selection.

—-

Image via the website of The Mexican Museum

[1] I’m both!

[2] My favourite books of all time.

[3] In most situations there are no “new” artefacts that fit these criteria, as most countries don’t allow the commodification of properly excavated antiquities. There is really no legal source of new antiquities. Only those excavated long ago work. This is where I tell people who want to collect antiquities legally and ethically that it’s best to find a new hobby.