Online information will disappear and it is CRITICAL that you archive what you use.

How do you prove that you know what you know? In academia, we do that by citing our sources. An academic citation shows that we aren’t just making stuff up, that what we are saying rests on information that rests on information that rests on information, etc. If the material that we draw upon for research or cite to support our assertions disappears, that is basically the crumbling of our foundation. The academic structure falls down. Put simply, if your sources no longer exist, I and everyone else will question if they ever existed. I might not believe you. You cannot afford this. You can depend on no one but yourself to preserve the information relevant to you.

Repeat this to yourself: the internet exists only in the present. The present may be your only chance to preserve what you see.

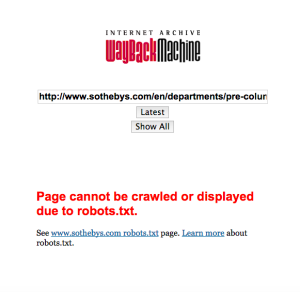

Horror story: during my masters in 2006, I observed that on the Sotheby’s Pre-Columbian Art website the auction house directly stated that they were scaling back public sales in favour of private sales. In other words, going underground and being more secretive about what was passing through their hands. That’s a pretty big deal and it related to a market pattern I identified. I didn’t save the page though and *woosh* that claim was gone. As far as I can tell they didn’t publicly acknowledge that this was part of their business strategy until recently. I didn’t print it out. I didn’t save the page. I am an academic who can’t back up her claim. It is my word against theirs that the statement was on their site.

Simply ‘not saving’ isn’t the only problem. Link rot, meaning when URLs cease to point to anything (404’d), is truly terrifying. Things are BAD. A recent study has shown that about 50% of URLs cited in US Supreme Court cases no longer work and over 70% of URLs cited in legal journals between 1999 and 2011 go nowhere. There should be a *record scratch* sound effect at this point because this is huge. What if 70% of the BOOKS cited in law journals no longer existed? Or imagine if no record existed of 50% of the legal opinions cited in Supreme Court rulings. This is big stuff.

You can’t pretend it isn’t happening.

In this post I’m going to show you all how I save and archive the online ephemera that constitutes a core component of my research into antiquities trafficking and art crime. I’ll show you the tools I use and tell you my thinking. This may not be the best way. This certainly isn’t the only way. But this is a way.

If you have any suggestions or improvements, email me about them and I can update the post.

Fighting link rot and saving online articles

To quote this must-read article in the Atlantic: “If a Pulitzer-finalist 34-part series of investigative journalism can vanish from the web, anything can”. Long story short: Kevin Vaughan wrote a spectacular piece with lots of online material. The paper he worked for went bust. The piece is gone. What you see online DOES NOT LAST and you should treat the moment that you are experiencing it as potentially the only moment you can experience it. Bookmarking it for later means nothing if it is gone (or modified later). If you ever need to use it again or if you have referenced it in any way, you need to save it. You. It is your responsibility.

Tools

- https://archive.org/web/

- Wayback machine bookmarklet

- Bibdesk (or other BibTex application)

- Save as PDF

- https://perma.cc/

- printer

- external hard drive (x3)

- cloud storage service

Methods

Say I’ve chanced upon this must-read article in the New Yorker about online information loss which states that “the average life of a Web page is about a hundred days” and I know I will need it again.

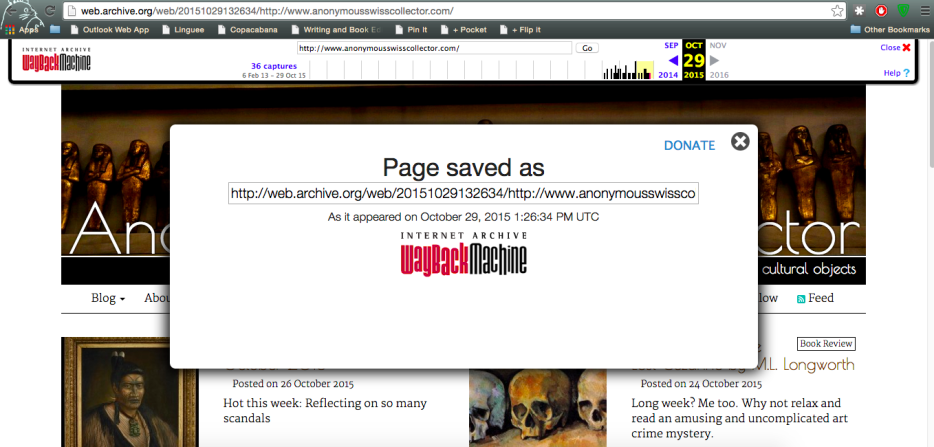

My very first step is to click on the WaybackMachine/Internet Archive bookmarklet that I have in my browser toolbar. With that one action I create a copy of the page as it is right then on archive.org. The article now exists in two places: on the New Yorker website and separately on archive.org meaning if the New Yorker crashes and burns tomorrow, the article will still exist on archive.org. This is the bare minimum that one can do. If you only think that you may want to read it again, not use it academically, you can probably stop at this step.

Note you can also copy and paste the link you want to save in at https://archive.org/web/ and avoid the bookmarklet.

I move to step two under certain circumstances: namely if the article is about anything within my core areas of interest. In this case, if the article is about any aspect of antiquities theft or trafficking or any aspect of art crime or related issues, I want to be in full control when accessing them again. I can only depend on me and I want my own copies in my own archive.

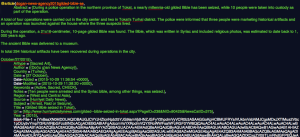

I use the application BibDesk as an article archival tool. BibDesk is, essentially, a convenient facade that sits on top of a BibTex “.bib” file. Bibdesk is appealing for several reasons. It is free. It is open source. That said, you can use any BibTex application you want, no worries. The resulting .bib file is non proprietary and easily convertible into any number of other file types (e.g. mine becomes a .csv file once a week) and can be transferred to another BibTex application easy-peasy if I decide BibDesk is no longer for me.

Via BibDesk I enter in the article’s basic bibliographic information. Then I add information that I deem to be important into a number of custom fields. This includes the archive.org URL of the article along with the original URL and some subject tags of my own devising.

I then save the article as a PDF. This is easily done in your chosen browser. In Firefox: File-> Print-> PDF (bottom left corner). I then drag and drop the PDF file into the relevant field in BibDesk. BibDesk then renames the PDF (I have it set to Year Author Title) and moves it to my PDF archive folder. This association, I warn, is a BibDesk thing, however, if I changed applications the filename of the PDF will still be associated with the bibliographic entry.

Post PDF, I copy and paste a plain text version of the entire article text into a special field in BibDesk. This means if all else fails, I have a full text of the article in the .bib file. It won’t be formatted. It won’t be pretty. But if my PDFs go and both links are broken, the info won’t be entirely lost.

Step three only comes into play if I am citing the article in an academic text. If this is going in a bibliography I save the article to another repository: perma.cc Perma is maintained by the Harvard Law School Library and has a growing list of academic partners. It may or may not be adopted by everyone in the future but there is nothing lost in getting on board now. Consider Perma just one more link backup for the very important things. This should NOT be your only copy; this one comes after the others.

And finally, step four, for the most important things ever. Print it. Hard copy.

I know this sounds like a lot of hassle and to some degree it is. But best practice is usually a hassle and without it things could go VERY wrong for you. The process goes rather fast when you are used to it. I do about 20 articles every day.

Backups

You have to back your stuff up. Obsessively. Thoroughly. If you aren’t saving in multiple ways and in multiple places, you are insane and negligent. I will just flat out say it. Here is my backup setup as it relates to online articles.

I have two portable external hard drives. One lives at home, one lives at work. These are where my PDF archive lives. When I save a PDF to my archive and associate it with an entry in BibDesk, BibDesk moves it to whichever of the external harddrives is plugged in. At least once a month I sync the two harddrives (I currently use open source FreeFileSync) and they become mirrors of each other. One travels with me when I go somewhere, the other stays safe.

Meanwhile, I have a big external harddrive that sits on my desk at work. It automatically backs up my laptop every hour. It also has a partition where the whole contents of the two portable hard drives live. I sync that perhaps every 3 or 4 months.

Finally, I use a cloud service to back up select folders on my computer and to store copies of irreplaceable files (which, of course, exist on all three harddrives), in other words PDFs of articles that I have cited academically. I currently am using Mega for this. I’ve previously used Spideroak.

Issues

Nothing’s perfect and nothing is permanent. There are some issues with archive.org that are worth noting. First, it will not save all sites. If a news organization has included a “robots.txt” file on their site they have basically told the Internet Archive to stay away and the Internet Archive respects that. News sites that include robots.txt should be first against the wall: they are monsters. If a site retrospectively puts in robots.txt, the Internet Archive will retrospectively remove what they had previously saved. In other words, a link saved to the Internet Archive COULD be scrubbed from it. That is why you save your own copy of anything that isn’t just a passing thing.

For example, let’s take the Sotheby’s Pre-Columbian website…the one that in 2006 confirmed that the auction house was prioritizing private antiquities sales. You might be thinking “Donna, why don’t you use the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine to find a copy of the old version of the page?” I thought of that too, dear reader, but alas Sotheby’s very predictably have included “robots.txt” on their website and so the record of that statement has been scrubbed. I didn’t save it, so it is gone. Just gone.

You also might be asking, what do I cite in my academic bibliography now that I have archive.org links and perma.cc links? Tough one. At the moment I don’t even bother with the original link. Instead, I cite BOTH the archive.org link and the perma.cc link. Yes, both. Not a single journal has called me out for including two links. Why not the original link? Well, the original link is WITHIN the archive.org link. The hope is that one of the three will work for whoever is trying to retrace my steps. And, of course, if none of the three work, that person can email me because I have my own copy.

Evaluating alternatives

Again, my system is not the only system, it is just what I have cobbled together. In evaluating alternatives, I recommend two things.

1. Stay in control.

If you are depending on a service of any kind to archive your stuff, what happens when that service folds? Your stuff goes down with it. In my case I have both a PDF and a plain text copy of every article that I need to save which I back up to my own devices. I am in control of those files. I depend on no one beyond myself to access them.

2. Stay flexible.

Related to staying in control. Use non-proprietary, open source tools which save your information in reasonable and widely used formats. Be able to pick up and leave your current applications for new ones at the drop of a hat. If you can’t do that, your system is vulnerable.

I am dead serious, you should care about this

Great power -> Great responsibility. We are currently living in a era of beautiful information but we have no idea what to do with it. Loss is constant and staggering. Most researchers and academics employ new tools but trust outdated archiving models. This is simply not an option anymore, if it ever was. If you are using online information in your research, you must self-archive it. It can’t wait another day.