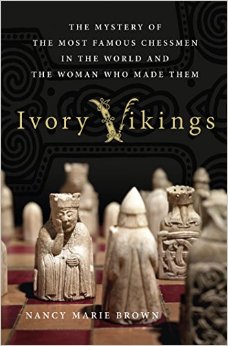

Who was the artisan behind the beloved, beautiful, contested Lewis Chessmen?

Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them

By Nancy Marie Brown

2015, St. Martin’s Press

A few weeks ago (August 2015), several Renaissance-period coins were stolen from the National Museum of Scotland. They were removed from their rather large case within the Kingdom of the Scots Gallery, perhaps during a time when the museum was open with only a skeleton staff and perhaps without anyone noticing they were gone for days. This is the second recent theft in the Kingdom of the Scots Gallery which raises serious questions about long term security of collections in a time where museums are being devalued and defunded.

A few weeks ago (August 2015), several Renaissance-period coins were stolen from the National Museum of Scotland. They were removed from their rather large case within the Kingdom of the Scots Gallery, perhaps during a time when the museum was open with only a skeleton staff and perhaps without anyone noticing they were gone for days. This is the second recent theft in the Kingdom of the Scots Gallery which raises serious questions about long term security of collections in a time where museums are being devalued and defunded.

What else is in the Kingdom of the Scots Gallery at the National Museum of Scotland?

The Lewis Chessmen: the most beloved and controversial artefacts from the end of the viking age. Eleven of them.

There is a lot for me to love about the Lewis Chessmen. Beyond their skilled execution resulting in worried queens, bored bishops, and shield-biting berserkers-as-rooks, they are at the root of all sorts of discussions of national and state identity and are a perfect example of the convolutions of claiming the past as one’s present property. We can all enjoy the Lewis Chessmen, but in building a set heritage identity around them, we hit several limitations:

1. They were only made in one place;

2. They were only found in one place;

3. They now have to be owned by someone.

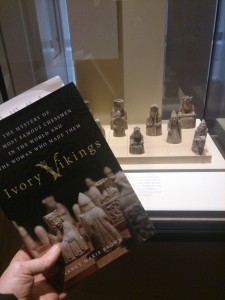

My copy of Ivory Vikings went to visit the ivory vikings themselves at the National Museum of Scotland.

Number 2 is uncontroversial in a broad sense. The pieces were found on the Scottish Isle of Lewis around 1831. Where on Lewis? Unclear, but Lewis it is. That means that the only solid place that can be ascribed to the Chessmen is Scotland, right? Well no. At the time the Chessmen were made the Outer Hebrides may not have been part of Scotland. Lewis joined Scotland via the Treaty of Perth in 1266 and were a Norse (but not Norwegian) Kingdom before that… the Chessmen are ‘probably’ 12th century. There goes that.

Number 3 is sort of a mess. For reasons (you’ll have to read Ivory Vikings), the National Museum of Scotland has 11 of the Chessmen and the British Museum has 78 of the Chessmen as well as 14 checker-like ‘tablemen’ and a belt buckle found with the hoard. Yes: most are not in Scotland and some people get upset about that, particularly people on Lewis who feel that the Chessmen belong near where they were found (and that Chessmen tourists should come to Lewis).[1] At various points the proper home of the Chessmen became a local Scottish National Party (SNP) issue, the ol’ politics of the past in the present. Imagine my amusement when, during the lead up to the Scottish Independence vote in 2014 various commentators brought up previous SNP comments on the Lewis Chessmen. “What would be the implications for the British Museum if Scotland voted for independence?” asked Charlotte Higgins in the Guardian. The thought of an independent Scotland, ancestral home of Lord Elgin, trying their hand at a British Museum repatriation battle had me giggling for days. Now THAT would be hilarious. If only.

Going berserk with a shield biting Berserker Rook at the National Museum of Scotland. Queen unimpressed

Now Number 1, where were the Lewis Chessmen made? This is the subject of the book that I am meant to be reviewing. In Ivory Vikings, Nancy Marie Brown fleshes out the argument that the Lewis Chessmen were made in Iceland and, specifically, made in Iceland by a woman: Margret the Adroit, an artisan mentioned in the Icelandic sagas who was attached to Skálholt Cathedral probably from 1195 to 1211. She worked in walrus ivory, which the Chessmen are made of. She was apparently spectacularly good at what she did, and the Chessmen are spectacular. She was working for someone who would be giving gifts, and Chessmen make snazzy gifts. She lived on one end of a trade route to the rest of the northern world, and Lewis was along that sailing path.

In other words: why NOT an Icelandic woman?

I very much enjoyed this book. It eventually served as ideal train journey amusement as I rode from Glasgow to Edinburgh to have another look at the real Chessmen. The chapters are themed as aspects of an individual chess piece. Berserker-as-rook for learning about the 12th century walrus ivory trade. Queen for the role of women and artisans in northern society. Bishop for religion and church. King for male elites and thus who might the Chessmen be for. Etc. It is very well researched for popular history: I learned quite a lot from the book but never felt like I was betraying my promise of not working on the weekends by reading it. By my standards, that’s the sweet spot.

It is true that Brown is writing in support of a slightly unpopular thesis. Most folks seem to like the idea of the Chessmen being crafted in Norway. There is absolutely no way to tell where these li’l guys came from, but Norway has emerged as the winner in most interpretations. Sure there are a number of near desperate attempts to have the Chessmen be from other places (e.g. people who REALLY want them to be from England and thus validate their presence at the British Museum), but for the most part people feel Norway is about right with Iceland as a reasonable runner up.

I did get a bit restless in my train seat near the end of the book when Brown discusses those who trash the Iceland hypothesis in terms of the academic establishment systematically excluding outsiders. That construction tends to be a classic sign of crackpotness, and what Brown has going on here isn’t crackpot at all. It’s quite solid and interesting. If I were reading the book before it went to print, I would kindly suggest she frame that section differently: if your theory isn’t crazy, you don’t want to sound like a crazy because we academics are only human. If the wording of an argument has certain ‘kook’ warning signals, it might get classed with the kooks. That section of the book left me wondering if the ‘Iceland origin’ idea may have had a poor reception because of how it was presented to my fellow academicians.[2]

But potential readers, don’t let my previous paragraph give you pause. Brown knows what she has is a theory and knows the limits of such things. She says herself that science can’t tell us who carved a chess piece and that with what we have now in the way of evidence, determining the location of the Lewis Chessmen workshop is impossible. Her solution? Fund archaeological digs. Yes. Fund them in Scotland. YES! Fund them in Iceland…although there are some complications on the site that needs digging as Brown rightly points out. The only way for us to know anything else about the Chessmen themselves and the time period they came from is to move some serious dirt.

Then again, as I said at the top, we’re in a period where funding for heritage is decimated with each passing year so awesome Chessmen excavations are unlikely anytime soon.

Ivory Vikings is a fun read about a fun topic: exactly the diversion I was looking for. Go for it!

[1] Six are back on Lewis as of last month!! Really, the BM has plenty of them. They are there “permanently as part of a loan agreement between Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and the British Museum”.

[2] She also assigns a lot of significance to curators at the British Museum not responding to communications from an Icelandic scholar. However this happens to all of us. I’ve had a BM curator not respond to multiple emails to multiple email accounts. I was only asking for a source for something they said on TV; it was never provided. The curator said they never got the emails and also kinda said they aren’t paid to answer emails (well neither am I). No BM response it isn’t a conspiracy, it’s just poor form.