My masters conclusion

Our fine University of Glasgow masters students must turn in their theses on Monday. To honour their struggle and their sleepless weekends, I am going to post the conclusion of my masters thesis (Yates 2006). It was fun to see it again. Chalk any mistakes up to youth. My writing has certainly improved since then.That said, I think I nailed it! Go team! Remember this folks next time I am looking for a job.

Yates, D. (2006), ‘South America on the Block: The changing face of Pre-Columbian antiquities auctions in response to international law’, MPhil Dissertation, University of Cambridge.

Available HERE

6. Conclusion

It would be easy to dismiss the South American antiquities auction situation as dire. As an archaeologist I am biased; looking at these catalogues was a painful experience. South American antiquities are not commodities like paintings: created for sale or public trade. They are not found objects that, by the nursery school rule of “finder’s keepers”, are wards of the finder to dispose of as they see fit. Legally, South American antiquities are the property of the people of South America. They are the icons of a glorious past and are seen by many as inspiration for a glorious future, thus instilling a sense of cultural pride in the poverty-stricken and oppressed. Personally, I cannot help but see the looting and sale of South American antiquities as evidence that the continent is being sacked yet again by western conquistadors who are destroying the past for money. Despite my biases I believe I have identified overarching issues within the market for South American antiquities.

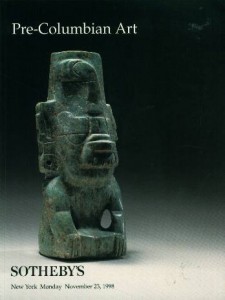

During the course of this project it has become painfully clear that, due to several factors, the objects presented in the Sotheby’s catalogues are unable to expand our knowledge of the past. The lack of context information renders the artefacts unusable for academic study and the air of doubt that surrounds the provenience information that is supplied only complicates the already obscure information about the object’s past. Some might argue that a piece that is divorced from its context can still yield information about the iconography and craft-making techniques of a certain culture, but almost any South American antiquity offered by Sotheby’s may be a modern forgery. As none of the artefacts encountered during the course of this study were excavated with their context recorded, one can not assume they are of ancient origin and thus any conclusions drawn about their iconographic and technical qualities would be highly questionable. Thus it can be concluded that the trade in these unprovenienced and most-likely illegal or illicit South American antiquities has actively prevented the public from becoming aware of the details of ancient cultures that could have been gleaned from the objects had they been properly excavated.

During the course of this project it has become painfully clear that, due to several factors, the objects presented in the Sotheby’s catalogues are unable to expand our knowledge of the past. The lack of context information renders the artefacts unusable for academic study and the air of doubt that surrounds the provenience information that is supplied only complicates the already obscure information about the object’s past. Some might argue that a piece that is divorced from its context can still yield information about the iconography and craft-making techniques of a certain culture, but almost any South American antiquity offered by Sotheby’s may be a modern forgery. As none of the artefacts encountered during the course of this study were excavated with their context recorded, one can not assume they are of ancient origin and thus any conclusions drawn about their iconographic and technical qualities would be highly questionable. Thus it can be concluded that the trade in these unprovenienced and most-likely illegal or illicit South American antiquities has actively prevented the public from becoming aware of the details of ancient cultures that could have been gleaned from the objects had they been properly excavated.

Due to the implementation of several forceful import bans, collecting unprovenienced South American antiquities is currently legally dangerous. The number of high profile seizures signals that that the bans are no idle threat. Despite this, the demand for the artefacts has not decreased. In fact, there is some evidence for an increase in the amount that buyers are willing to pay for South American objects which may indicate a greater demand. Despite the apparent profitability of the South American antiquities market, Sotheby’s reduced the number of artefacts they offered to a trickle in 2001, choosing to broker undocumented private sales. This cutback seems to be a result of the various scandals that hit the company at the time. Although the international agreements that came into effect may have been a factor in this cut back, they were most likely not the only factor. The tendency for archaeologists to see antiquities as outside of the normal art market and the internal issues of the auction house may result in researchers missing key information as to why changes occur in the market. The isolation of only one antiquities class sold in a larger auction, as seen in previous studies of this sort, is problematic as well. A mysterious decrease in the number of Maya objects sold in a particular years as documented by Gilgen in 2001 appears to not relate to import restrictions as suggested, rather to an increase in the number of South American objects sold at the same auction. We cannot continue to divorce the lots from their auction and full catalogues must be reviewed by researchers for mean ingful conclusions to be drawn.

I do not wish to outright accuse Sotheby’s of anything illegal. I have merely highlighted ways that Sotheby’s, through opaque business practices and vague information, could have been deceptive in their dealing of South American antiquities. It cannot be forgotten that Sotheby’s does have a long history of deception and illegal practice (see Watson 1997 for art and antiquities smuggling, Rose 1996 for the sale of banned antiquities, and Mason 2004 for anti trust violations). I believe that Sotheby’s have earned their notoriety. Their sale of South American antiquities could be clean, but it is not. It could be transparent, but it is not. They could sell only properly provenienced objects and objects with clear ownership histories, but they do not.

I also do not wish to condemn the legal trade in antiquities. Though I, personally, do not understand why anyone would want to own an unprovenienced antiquity when one can easily visit museums or participate in archaeological digs to commune with the ancients, I acquiesce to current legislation. If an antiquity legally left its country of origin, legally entered its country of sale, and is sold publicly I feel that interested parties should be allowed to buy. There are a limited number of antiquities that were collected long ago and are now gathering dust in attics. It seems cliché to say so, but they do turn up in old family collections.

In a sense, public auctions have been a blessing when it comes to the study of the antiquities market. Catalogues show what has surfaced, what people wish to buy, and what they will pay for it. The movement towards private and undocumented sales as uncovered in this study is truly frightening. It appears that we may no longer have the invaluable resource of auction catalogues to gauge what is truly going on in the South American antiquities market. A new strategy must be developed to track these objects and root out illegal practice before the market descends deeper into the dark recesses of back door deals and international crime.

A number of issues remain unresolved and, in a sense, this preliminary study of the particulars of South American antiquities auctions has raised more questions than it has answered. Clearly the Sotheby’s South American antiquities auctions that still occur should be tracked in the future for any indication of a change in the patterns detected by this study. Research should extend, if possible, to private dealers and online auctions as there is evidence that a significant trade in moderate quality South American antiquities exists within these realms. The particulars of Sotheby’s private sales of South American antiquities should be investigated as they represent a significant deviation from the ideals of an open and transparent market. Museum acquisition records should be consulted to see if patterns on the supply end do, indeed, match patterns on the demand end of the antiquities market. Perhaps most importantly, more similar studies of classes of antiquities sold at auction should be completed so that a more detailed understanding of the demand for artefacts emerges. The creation of this database is a step in the right direction, but I hope to address the wider concerns uncovered by this study in future research.