A guest review by Diana Miryong Natermann

Restitution in the Netherlands and Belgium

by Jos van Beurden

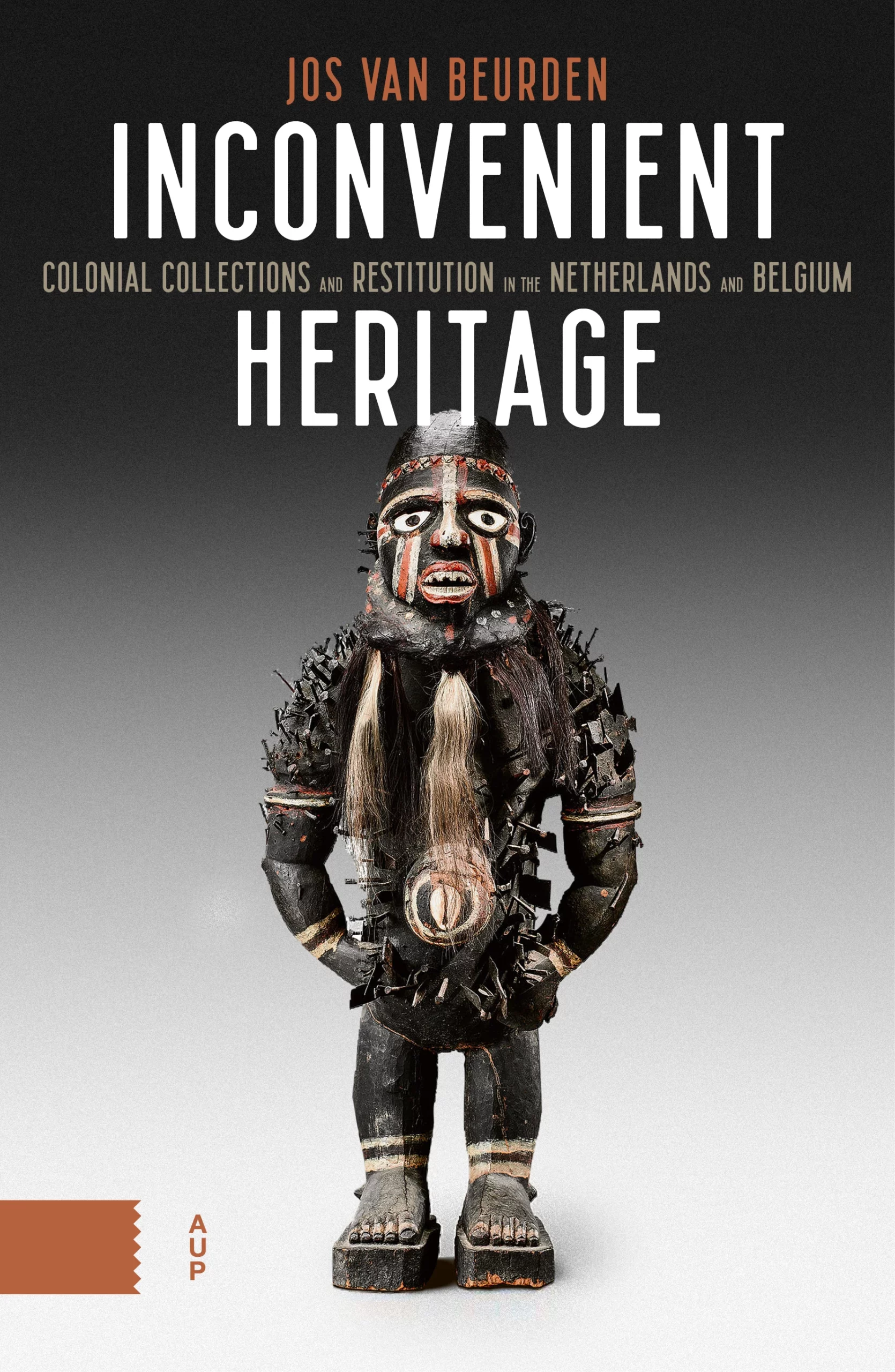

2022, Amsterdam University Press

Jos van Beurden’s book Inconvenient Heritage. Colonial Collections and Restitution in the Netherlands and Belgium (Dutch original: Ongemakkelijk Erfgoed. Koloniale collecties en teruggave in de Lage Landen, Walburg Pers 2021) presents an overview and historical analysis of two Western European countries – Belgium and the Netherlands – with impressive colonial pasts in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It discusses how a significant part of art heritage from overseas territories has made its way to European museums and how to engage with them in the years to come. Given their histories, most of these objects were transported to Europe without the makers’ and users’ consent. In line with past and current developments, museums, art dealers, collectors and historians in and from Belgium and the Netherlands are dealing with how to readdress colonial injustices like the removal of cultural heritage from the colonial peripheries to its metropoles. Especially the last decade has also seen a spike in wider public interest too in the debates around colonial collections.

The book consists of five parts and fifteen chapters (with three or four chapters per part). The first part – A Decisive Phase in an old Debate? – is split into four chapters. It introduces the reader to the history of the restitution debate since its tentative beginnings in the Cold War and decolonisation era of the second half of the twentieth century and ends with highlighting some tentative but important developments in the past decade. Chapter 1 to 4 provide a brief overview of collecting practices during colonial times that represent the beginning and continuation of non-European cultural and everyday objects to Belgian and Dutch museums. This is followed by a discussion of how attitudes towards colonial objects in Belgium and the Netherlands have changed in the past ca 60 years. One reads about the growing interest in how objects from colonial contexts came into European hands in the first place and how difficult it is to retrospectively establish the how and why of their arrivals in Europe. The fourth chapter explains why museums tend to lack sufficiently detailed information and reliable primary sources on the transaction procedures. This provenance data is lacking which proves to be particularly painful concerning finding solutions for the return of human remains like skulls and bones.

Part 2 – Thrifts Returns in the 1970s – consists of three chapters that present a selection of difficult attempts at restitution from the 1970s onwards with the first case referring to the return of an Indonesian Kris that had belonged to Prince Diponegoro. A Kris was a stabbing weapon and Indonesia has been requesting it back since 1975. The second case study engages with how the Belgian government and the Musée Royal de l’Afrique Central (MRAC) in Tervuren maneuvered through and around restitution claims of the Congolese President Mobutu Sese Seko in 1973 during a General Assembly of the United Nations. In the end, Belgium and the MRAC returned 114 objects; however, they were generally of little aesthetic and cultural-historical value. The only exception being a wooden statue of the King Bope Kena of the Kuba people. Further examples relate to Suriname and the former Netherlands Antilles. For instance, how the Ethnological Museum in Leiden and the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam returned some of their objects from archaeological excavations to Curaçao and Aruba in the 1980s. Other returns took place in 2006 when Suriname received a replica of a Maroon chair and between 2010 and 2017 the National Archives in The Hague returned parts of its colonial archive to the archives in Paramaribo.

In Recent Returns – part 3, chapters 8 to 11 – the more recent returns of human remains and archives are discussed. The first example elaborates on how the Volkenkunde Museum Leiden returned Maori human remains to New Zealand. This is followed in the next chapter on how Rwanda and Indonesia received objects from Belgian and Dutch archives respectively either in microfiche or digital forms. The author van Beurden then continues to present the difficulties in returning objects to Indonesia faced by the closure of the Nusantara Museum in Delft in 2013, which had had a collection of 18,576 objects. The sale of this collection was accompanied by high tensions when it turned out that not Indonesia, but the city of Delft as well as former donors, borrowers and a number of experts appointed by the Dutch state were given the privilege of making a first selection for themselves. The eleventh chapter presents the famous Benin bronze works that British soldiers looted from the Kingdom of Benin in 1897 and were then sold off all over Europe and Northern America. Being Europe’s first continent-wide collaboration on restitution and repatriation, the Benin Dialogue Group (BDG) is treated as a potential blueprint for other future restitution alliances. Within the BDG several European countries entered into negotiations and consultations with Nigerian authorities to discuss and see through the return of Benin heritage objects.

Part 4, Private Collections – Less Visible, But not less important, consists of two chapters and the reader is introduced to those collections that were created and owned either by missionaries, missionary congregations or private individuals. It highlights the difficulty of getting a realistic grasp on how many more colonial objects are still available in private homes, church cellars or random attics. Even the possibility of some pieces being thrown into the dump after the closure of museums, churches or heirs not liking the inherited objects need to be acknowledged. Such losses are to a certain degree part of any heritage objects.

Finally, the book closes with its fifth part – Towards a new Ethics – and the question whether or not there is a new ethic engagement with colonial collections and questions of restitution. As is to be expected, there is no clear but rather a hesitant and carefully weighed answer. Restitution is not always the right answer to correct colonial aggressions. At times, the formerly colonised constituencies do not want their heritage returned but simply destroyed. In other cases, a return instigated by former colonisers without prior collaboration with the formerly colonised is seen as yet another colonial act.

Overall, the book is very readable which I would argue stems from two main points. Firstly, the autobiographical path it partially follows based on van Beurden’s earlier engagement in the fight against illegal art trade. Secondly, the book informs its readership about the opinions of various actors involved in restitution debates and lets the readers come to their own conclusions on the issue. Even so, one wonders what is or has happened on the issue besides the author’s view both within and without the Belgian-Dutch context.

Ultimately, van Beurden succeeds in presenting the complexity that comes with restitution debates. He does this by discussing the most important question of who is entitled to receive restituted objects in the first place? National museums in a country of origin? The heirs of those to whom the objects once belonged? Does every collection with a colonial history have to be returned? Despite addressing these questions, the book lacks a more thorough engagement with a definition of what heritage is. How does heritage come to be and how does it change over time? And which factors influence the process of an object becoming part of a culture’s heritage? Chapter two, for instance, gives some examples on heritage objects but the comparison made therein is too simple. Since the understanding or evaluation of heritage usually changes over time so does the question of who shall receive restituted items. Linked to this, van Beurden’s often repeated goal to undo colonial injustices sometimes sounds illusory since any returned object is no longer what it was when initially taken by the colonisers.

A strength of the book is the author’s plea for more funding and attention to provenance research, emphasizing the importance of collaboration with local experts and communities from the countries of origin. The monograph highlights the need for public outreach, acknowledgement of colonial aggressions are vital and collaborative efforts for reconciliation and healing. The vast amount of images in the book also helps underline the diversity of objects, people and locations involved in this process.

Inconvenient Heritage fills a gap in the research field by focusing on the Belgian and Dutch contexts, which are still less explored compared to French and British agendas. Whilst the book has some loose ends – eg. the lack of definition of what the term heritage entails or more information on why provenance research in Europe is on the rise – it is still a well-written book that easily weaves together different eras, political systems and countries. It appeals to both academic and non-academic audiences and contributes to the ongoing discussions and actions surrounding colonial collections and restitution.