Over 50 years old and still a useful and interesting read

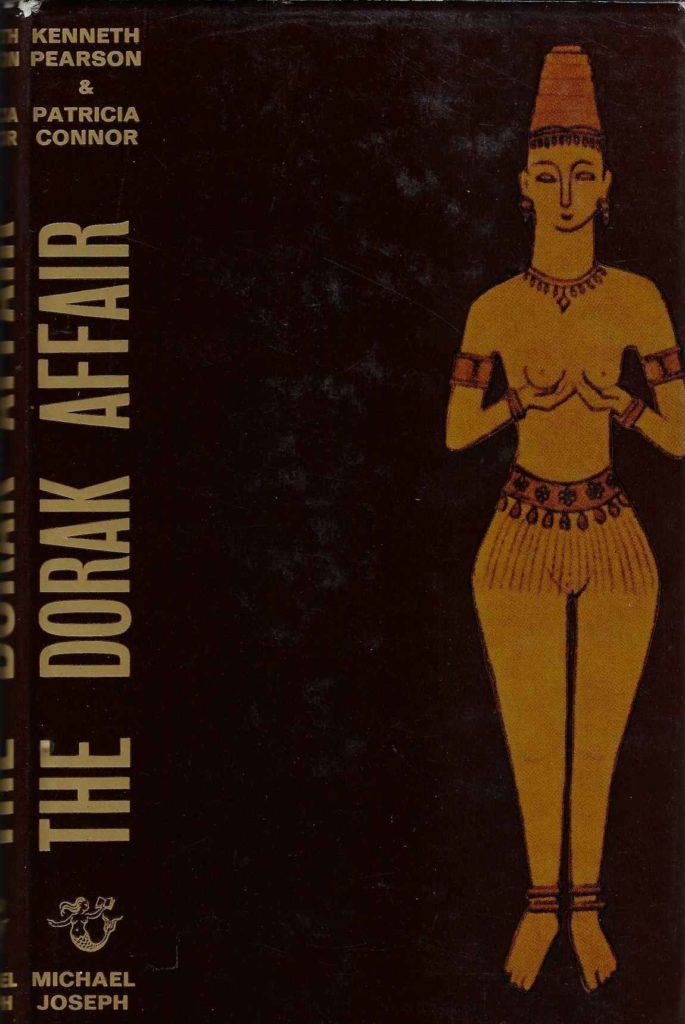

The Dorak Affair

by Kenneth Pearson & Patricia Connor

1967, Michael Joseph

I know what you’re thinking: “Donna, I see the date you typed above, this book is over 50 years old. How is this relevant to anything?” Well, dear readers, I confess to thinking the same thing which is probably why I haven’t read The Dorak Affair until now. If I ding my students for dusty bibliographies, what could I gain from investigative reporting into antiquities trafficking from half a century ago?

A lot actually. A whole lot. A “dear gosh I could have used this book so many times in the past” lot. A “now I really feel silly” lot. A “people have been writing the exact same thing I have to write for over 50 years and yet nothing changes” lot. Are you going to see The Dorak Affair in my bibliographies from now on? You are.

If you, like me, haven’t yet read this book just take a pause right now and head over to your preferred online used book vendor and buy yourself what is inevitably going to be a shockingly cheap copy (e.g. I see it for $3.66 on US Amazon). It is also probably in a library near you, according to WorldCat. Order or request your copy now. You want to read this book.

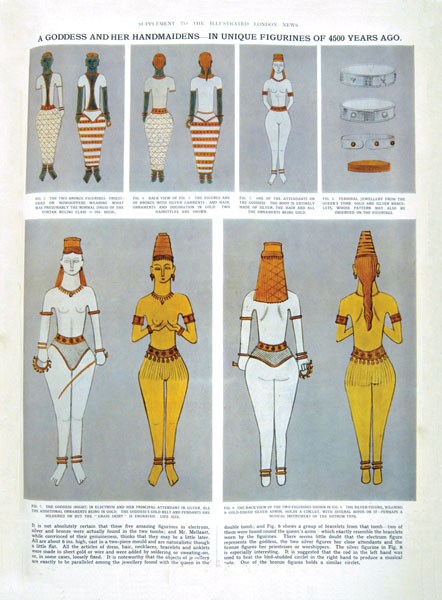

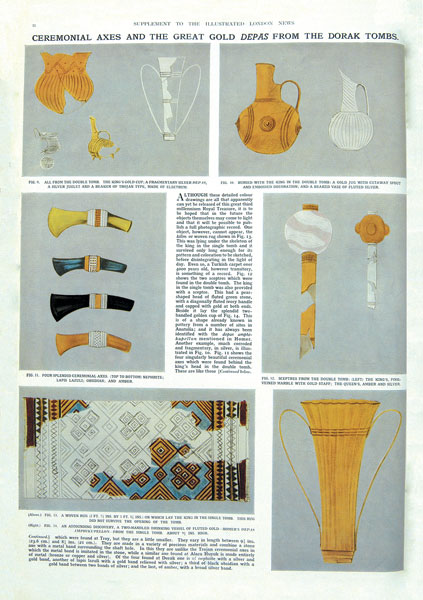

So what is The Dorak Affair? Put simply, it was a swirl of allegations against famous Çatalhöyük digger, archaeologist James Mellaart relating to what he claimed was a spectacular collection of antiquities that proved his ideas of ancient people from Turkey being the so-called Sea Peoples. Mellaart claimed that he met a young woman on a train, was attracted to the ancient gold bracelet she was wearing, and was taken back to her house in Izmir to see a massive collection of ancient items that she said was illegally looted near a place called Dorak. The woman then allegedly let Mellaart stay at her house for several days and nights, drawing the antiquities, but didn’t allow him to take photographs. Mellaart says he didn’t know and didn’t note where the house that he stayed for days at was, and that he didn’t bother to ask the woman her name until he was leaving. Mellaart never heard from the woman again, save (he claimed) for a short typed letter giving him permission to publish his drawings of the Dorak Treasure. No one has ever located the woman in question. The antiquities have never surfaced on the market or in any known collection anywhere.

You can, perhaps, see why commentators thought Mellaart’s story was a bit hard to believe.

Some of Mellaart’s Dorak Treasure drawings

After the Dorak story broke, various people in Turkey accused Mellaart of engaging in antiquities trafficking. They claimed he was the true discoverer of the Dorak items, that he smuggled them out of the country, and that he made up an absurd “anonymous woman on a train” story to provide cover for his publication of drawings of the treasure. This tanked Mellaart’s Turkish archaeology career and resulted in Çatalhöyük excavations being shut down until 1993. Meanwhile others accused Mellaart of faking not just the story, but the Dorak artefacts themselves. This camp believes Mellaart used his vast expertise to create a fantastical group of artefacts that supported his theories about the past. A small minority felt that Mellaart was set up by someone who planted the woman on the train for nefarious purposes. Nearly no one thought that things went down as Mellaart said.

In this swirl of confusion, allegations, theft, and forgery, British investigative journalists Kenneth Pearson and Patricia Connor appeared on the scene in Turkey. Their assignment: to uncover what they could about the Dorak scandal by conducting a wider investigation into looting and trafficking of Turkish artefacts. And that they did. Several years before the UNESCO convention, at a time when current market actors claim that no one knew or cared about looting and the law, these folks not only wrote a very popular and successful book on the topic, they recorded in that book that EVERYONE knew about looting and a lot of people cared.

At the heart of this book is a strange and interesting story, well-researched and told in a way that brings the reader in to the hunt for information. I was hooked from page one and didn’t set this book down until I had finished the thing. It is a good read. Aside from the usual frustrating gendered writing in places, you won’t feel it is 50 years old. I could sit here and type line by line the bits of this book that I’m totally going to be citing later, but I think that does this work a bit of a disservice. It’s fun to read.

The book has some special perks for heritage crime nerds. Chief among them was the appearance of a young Aydın Dikmen as a local shady guy who seems to have antiquities that he shouldn’t. Dikmen, who later moved to Munich and died in April of this year, would go on to profit from the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus by selling looted church mosaics. The Dorak Affair was on to Dikmen before Dikmen hit the transnational crime big time. Clearly the authors were talking to the right people.

Producing a spoiler-free review of a 50-year-old book is very hard to do. What I can tell you is that neither this book, nor the passage of time, have produced a definitive answer to the Dorak questions. However, since his death in 2012, much more information has come out about James Mellaart which provides context that the authors of The Dorak Affair didn’t have. If you possibly can, don’t read this very recent information about Mellaart until after you’ve read The Dorak Affair. It is more fun to follow the case that the authors present and then get your update afterwards. The afterwards update is pretty juicy so you’re in for a scandalous treat there too.

Perhaps I’ll spend my autumn only reading art and heritage crime books that are older than I am.