It’s likely ‘smaller’ than people think, but this report doesn’t show that

When the World Customs Organization Illicit Trade Report 2019 came out a couple months ago I put it on my agenda to review in this blog. However, after a few days of thinking about it, I decided not to do the review. While the report offers an interesting window into the illicit trade in cultural objects, there are just too many caveats, footnotes, and background needed to understand the severe limitations of the data presented. I was afraid some would get confused by the report and decided to leave it for my academic work.

Well, looks like someone got confused:

“A New Report on Transnational Crime Shows That the Business of Smuggling Cultural Property Is Not as Big as People Think“, by Ivan Macquisten, Artnet News, 28 September.

This article was a painful read. Mr Macquisten is clearly trying to scratch at something important here, but he (and his editors) totally fail to grasp the limitations of the WCO report. The headline is manufactured from a flawed analysis of the data within the report and a total lack of understanding of the context and conditions under which the data in question was collected. It is clear that Mr Macquisten neither contacted the WCO nor anyone working on/with customs in this area to try to understand what was presented in this report, and the result is a total misunderstanding of 1. Data Quality and 2. Data Comparability.

Please understand this is not a criticism of the WCO report. The WCO is clear about the limitations of the data. This is a criticism of an article written without a full grasp of those limitations. Also, I am not going to rehash the article. Read it for yourself before going on. Now’s a good time.

Meanwhile, two things:

First, as I said above, *I AGREE* that ‘the business of smuggling cultural property is not as big as people think’, provided big is defined as monetary value. Over the past decade, absolutely groundless media articles have reported the annual value of the illicit trade in cultural objects in increasingly absurd numbers, to the detriment of everyone. I remember a few years back, when the totally-baseless media figure hit $6 billion for the illicit antiquities trade, I had a joking email conversation with another professional in the field speculating that now was the time for us to switch sides, with my smuggling expertise and their market connections, we could have our slice of that (NON EXISTENT) pie. I think that the bulk of the antiquities trade is made up of small, low value pieces that are easy to smuggle, nearly anyone can afford to buy, that evade detection or fall below value minimums set in law, and whose extraction from the ground is just as destructive to the past as that of a €1mil piece. Again, *I AGREE* that there is a very wrong impression out there about the nature and monetary value of the trade in illicit cultural objects, it’s just THIS WCO REPORT DOES NOT SHOW THAT.

Second, in recent years I have been involved in research that touches on issues involved in reporting and investigating cases of cultural object trafficking (e.g. see this European Commission Report). That subject has not usually been my particular focus within the research, but read all the interview and survey data we collect on the topic. I also am on friendly professional terms with people working in customs and law enforcement in this area, I am in regular contact with the WCO office in question, am currently working on some digital training for customs officers and shippers, and I comb reports like this as a regular part of my research…in other words I spend a lot of time thinking about this type of data. I am not claiming expertise on customs operations here, just giving a bit of a resume for my reading of the report. ArtNet simply doesn’t have that kind of background and they should supplement their own expertise by talking to an expert before they print such an article.

Now into it:

Data Quality

The numbers presented in the WCO report are limited and incomplete. WCO member countries are not required to submit data for this report, and all data submissions are voluntary. How incomplete? Well there are 183 members of the WCO (175 countries, 4 customs territories, and one customs union). Of those 183 members, 34 contributed to the cultural object section of the report: 18.6%. Cultural object seizures in 81.4% of WCO countries are not reflected in the report. That alone should stop anyone from seriously considering this a complete view of trafficking in a certain type of object.

Looking at this list of countries included, at first glance we see some major market countries (e.g. the US, UK, France, Germany), but some notable absences (China[1], Netherlands, Belgium, Australia, etc.). Also absent are significant antiquities source countries that are likely to stop objects on their borders (Egypt, Mexico, Nigeria, Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Cambodia, India, etc.) and known antiquities transit countries that the objects pass through on their way to market (Turkey [1], Lebanon, Switzerland, Israel, Brazil, etc.). You know those places that are in the news all the time making antiquities busts? Those aren’t in the numbers.

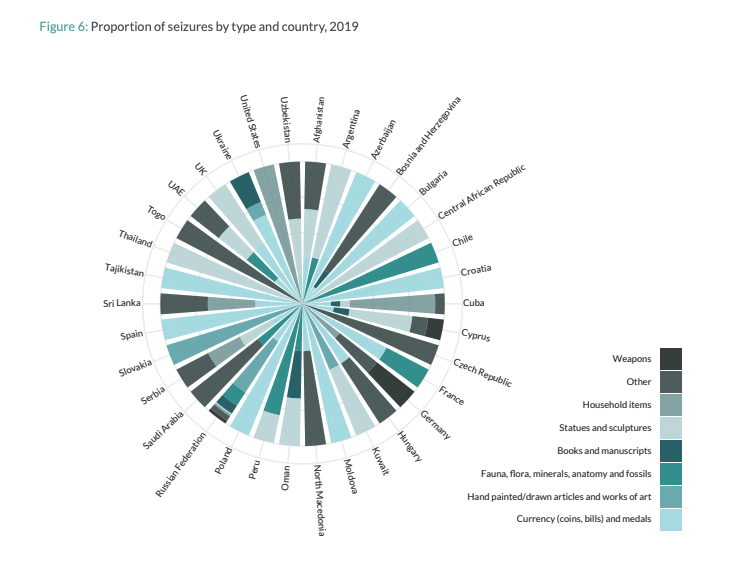

Next, if you look closely at the chart above, you’ll note some strange things. For example, the entirety of what the US reported as cultural objects falls under the category of “household items” and other charts indicate that this is less than 20 items, so <20 cultural objects seized by US customs in a year; no “statues and sculptures” or “works of art” seizures reported by the US. These are demonstrably incomplete numbers for the USA for 2019. Doing a news search and taking, literally, the first article that popped up, in 2019 US Customs and Border Protection seized scraps of mummy linens in a Canadian mail truck. I don’t think any mental contortion can make these mummy linens into “household items”. There are scores more news stories available like this for 2019. My point being that even the countries that self-reported for this report did not report everything (and, at times, hardly reported anything).

The issue, then, is data quality and specifically the quality of the data in the report as it relates to answering the question “how big is the illicit antiquities business?” The data in the report cannot be used to answer that question. It is simply too low quality.

Without going into too much detail, I’m going to list some of the issues that contribute to that low quality data:

- Reporting to the WCO is extra work and customs agencies often do not have the time or staff to generate specialist category reports that do not reflect their internal classification of object seizures.

- Many seizures aren’t made by customs, rather by Law Enforcement Agencies of various kinds (you know, the police). All those seizures are not in the WCO report.

- Lack of any data from countries along known smuggling routes and where we know major seizures were made in 2019

- and sort of an aside here, seizures are not a direct indication of the size of an illicit trade. They indicate that an illicit trade is happening, but a successful smuggling operation is, by definition, not caught.

Data Comparability

Another trap that the ArtNet article falls into is trying to compare this incomplete data to other data in the report. That other data is incomplete as well, so we end up with a comparison of two sets of incomplete data and an insistence that the results are meaningful. Let’s quickly look at issues of data comparability.

Within just the reporting of WCO data on cultural objects alone, the data presented for each country is interesting, but simply cannot be compared to the data from other countries in any meaningful way. Yes, I can look at this report and say Russia is stopping some amount of “Hand painted/drawn articles and works of art” from entering or leaving its borders, but I am unable to compare that to the US’s apparent lack of the same. Why?

- Every country has a different legal definition of what cultural objects are, e.g. some include fossils as cultural objects. This skews the numbers and makes country to country comparison impossible

- Some countries only report completed cases to the WCO while others report all cases. Cases can stay open for years.

- Some countries only report seizures of major, high value items; low value cultural objects may even fall under mandatory investigation minimums

- Some countries have poor measures in place for detecting cultural objects in transit and simply don’t detect many objects: traffickers tend to know the weak countries and route items that way

- Many countries have no separate reporting category for cultural objects and no internal tag for cultural object cases. They don’t keep stats on cultural object seizures and can’t report those seizures when asked.

- Also, of course, reporting is voluntary for the WCO and even the countries that did report chose not to report (in some cases) most cultural object seizures for 2019

Moving outward a bit, the ArtNet says that since the WCO report covers 36,264 drug cases, 28,000 counterfeit good cases, and 26,000 alcohol and tobacco cases, and only 227 antiquities cases, it evidences the “insignificant scale of cultural heritage crime”.

Oh dear.

Come on bullet points:

- The countries that reported data about drugs, booze, and fakes to the WCO are NOT the same countries that reported data about cultural objects. Many more and different countries reported on these other illicit things.

- Drugs, counterfeit goods, and alcohol/tobacco cases are front line, top of the top, priorities for basically every customs agency in the world. They get the most training focus, the most money, the most internal specialist attention. Customs is designed to find those things.

- Because they are top priorities, customs collects massive amounts of data on these types of illicit goods, automatically. They have special tags, special reporting categories, and they report them to their governments, the public, etc. The numbers are crunched and compiled and are easy to then pass on to the WCO.

- The bounds of what constitutes a counterfeit goods case or an alcohol or tobacco case are very open and, YES, more people commit those crimes, due to the nature of those crimes. You bringing one extra bottle of wine from France to the US and hoping for the best is an alcohol case. Me buying a “Nokia” phone in Bolivia in 2013 (so I had something for my local sim card) and bringing it to the UK after is a counterfeit goods case. Just wait until the post-Brexit UK realises they won’t be able to casually smuggle excessive cheap cigarettes from Central Europe anymore.

Wrapping up this rant

Look, I have to interview people about fossils today because that’s just what I do, I need to stop ranting about this. However, it just gets me when a report is so poorly used and incomplete data is pushed towards supporting a hot-button assertion that it simply doesn’t support.

Again, I want to assert that I agree with the sentiment of the second half of the headline: the numbers put out there for the financial size of the illicit cultural object trade are unlikely and are not supported by research or market data. However, you just simply can’t push this WCO report into being evidence for that. You can’t do it. It doesn’t work. It is wrong, lazy, and damaging.

ArtNet, listen to me: you can’t do it.

[1] The report doesn’t give a good list anywhere of exactly which countries participated, and the chart in this post seems to be the only list: it has the right number of countries as reflected in the text. However I note that at one point in the text, Turkey and China are listed as being reported as “an origin, destination, or transit point”, but that doesn’t mean either of those countries provided data, rather it seems one of the other countries that did report included info that Turkey or China were involved in the objects seized.