The history of this controversial painting is the history of everything weird in the art market

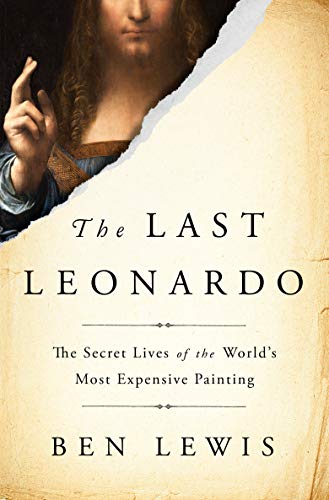

The Last Leonardo: The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting

by Ben Lewis

2019, Ballantine Books

Oh boy, oh boy. The Salvator Mundi. Oh me on my. What a spectacular swirling storm of nearly everything that can go weird with the art market. Questionable provenance, authenticity issues, Russian oligarchs, free ports, misrepresentation, back door deals for profit cuts, Saudi princes, full on fraud, and “value” as an intangible unpegged to reality with buckets of money to follow. Oh boy, oh my.

For the past three years I’ve find myself unable to look directly at the Salvator Mundi case. I have had a busy time of late and I felt I wasn’t ready to sort out all of that in my head. Too complicated. Yet, thanks to Ben Lewis’ well-researched and carefully written book, following the interwoven strands of this painting’s history was not stressful but pleasurable. It takes hard work to make this story so smooth and readable, and Lewis accomplishes that. Lewis has done all the real work so that I didn’t have to, I just sat back and let the story unfold.

For those of you who somehow missed 2017, Christie’s sold a painting that they and some asserted was by Leonardo for over $400 million, making it the most expensive painting ever sold at auction. In the lead up to this sale they went on a major hype spree, placing it in the popular press, making promo videos, etc etc. Their work paid off, obviously, and (as the book relates) all sorts of people made a lot of money on the sale.

It seems like the obvious point of criticism here is the price paid. It seems insane because it is. Yet there’s an odd logic to it. You see, real Leonardo paintings don’t come up for sale ever. Really, never. And people really like real Leonardos. So if you are someone who wants to have a real Leonardo, an astronomical price for something that is a market near-impossibility makes sense. Okay.

But here’s the real problem. Is this a real Leonardo? Many (many, many) people don’t think so. Why don’t they think so? And what is a “real” Leonardo anyway? Well, that’s were “The Last Leonardo” comes in.

Lewis’ book is structured around two timelines running in parallel: one runs from the point that this painting is bought at a small Louisiana auction house for less than $2000 USD in the early 2005; the other follows the provenance of the painting from the 16th century to that Louisiana sale. By blending these two pathways, these two lives of the painting, readers of “The Last Leonardo” are able to see how the past of a painting has a direct effect on its present, and are able to appreciate the gaps and issues that the author so carefully defines.

From this book I learned that the world is awash with Salvators Mundi, and has been for centuries. The artists within Leonardo’s work shop pumped out Salvators based on a set design with none of them signing or dating their paintings. Those then were scattered around the world and misattributed to Leonardo himself or to the wrong Leonardo follower. They were then copied by later artists, and those copies, themselves, got misattributed. They were also restored poorly, with terrible overpainting, leaving them in a state where, perhaps, significantly more restoration exists than original painting.

Which Salvator Mundi is the original Leonardo, the painting that launched a thousand follower copies? Well, as “The Last Leonardo” demonstrates, there isn’t much in the way of proof that it is the one that was sold at Christies.

Further, even if it IS the Leonardo-est Salvator Mundi (whatever that may mean within the realities of Leonardo’s workshop), there’s significant concern that much of what was visible to anyone who stopped in to see the painting while Christie’s was hawking it is restoration. The painting was in such terrible shape when it was bought in 2005 that there are plausible allegations that up to 80% of the original painting is gone, and that the buyer got 20% Leonardo (or follower) and 80% the 21st century restorer.

This is starting to not sound like a solid investment of $400 million.

I found the book hard to put down at times: I spent the past few days holding the book in one hand and watering the garden with the other. The twists and turns of the provenance of this painting exemplify art market crazy from day one, from the moment it was made within a workshop setting where authorship was already fluid, possibly in a way that Leonardo’s patrons were not always cool with. Every time something goes odd in this painting’s history, it goes odd in the most “of that moment” way, from the overthrowing of kings, to the fleecing of Russian multibillionaires. The Salvator Mundi’s story becomes the history of the art market itself; it isn’t just a “how did the painting get here”, it is a “how did we all get here”.

And, as Lewis points out in his fine final chapter, we got here not because the art market changed, we got here because it hasn’t changed. We are wading through the same strange and opaque mess that the art market has always been, just adjusted for inflation.