On forfeiting expertise and integrity to support the commodification of cultural objects

At least once every two months I receive an email offering me antiquities for sale. I can never quite tell if the person contacting me about these is just remarkably dim or if they’ve just opened the flood gates to whoever matches a few internet search terms. Either way, I would have thought that even a sliver of my online presence would preclude me from direct marketing of stolen art, but apparently that’s not the world we live in. Lately I’ve been offered, among other things:

- Old Persian books, still in Iran, to be delivered to my embassy of choice

- Amazonian weaponry

- Coins, coins, coins…usually with dirt still on them

- What someone was claiming to be dealer Giacomo Medici’s trench coat

Alongside these amazing offers, I am contacted by a variety of people asking me to “offer my opinion” about various cultural objects that they own, could buy, or have photos of for mysterious reasons. This happens more often than the direct sales pitches: people seeing my authentication as an antiquities expert for various purposes. Many of these are well-meaning and fit into a number of set categories:

- I see this for sale online and I’m worried. Is it real? Can you do something?

- I just inherited this antiquity and my loved one left no records about it. Is it real? Is it illegal?

Others are less well meaning:

- I want to sell this thing, would that be illegal?

- I see you’re an expert, can you authenticate this thing for me?

- What do you think about [pictured]? (no further details offered)

Some of you may have noticed that in the FAQ section of this websites I note that I do not authenticate or offer opinions about individual antiquities to anyone but the police, customs, or other competent authorities. I often will drop everything to help out an official investigation, and will go as far as I can within the bounds of what can be said about a photo to aid in those. However, I will under no circumstances whatsoever provide any opinion at all to anyone else in possession of a suspect antiquity. For well-meaning people who contact me my two responses are, as appropriate, “contact a lawyer” or “contact the police”. For everyone else, from those trying to sell me something to those wanting to get my OK for buying loot, they get no response whatsoever.

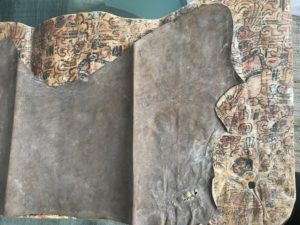

No response is often very difficult, I’ll tell you. “ARE YOU STUPID? YOU MUST BE STUPID. I’M REPORTING YOU TO THE POLICE.” Seems like a fitting response to people trying to sell me stuff, but even if I can follow through with a police report, it’s not on me to tell them I’m doing that. And for the authentications, again, “Yeah well that ‘Maya Codex‘ that you’ve attached photos of [right] is about the fakest thing I’ve ever seen and you should be a bit embarrassed that you were taken in.” is a fine rage response, but is hardly professional. Plus a negative authentication is still a professional opinion. Dude who sent me photos of the ‘Maya Codex’ last week who I didn’t respond to, sorry to use you as an example (although you ignored my FAQ on the topic), but COME ON, SERIOUSLY?

The issue of authentication is a big one in the field of Archaeology, with both archaeologists and museum professionals falling on different sides of a pretty deep canyon on this. Some archaeologists and museum professionals feel that the process of authentication for a member of the public is a point of contact where we can possibly educate the bearer; we can, perhaps, point them in the direction of good. However others fear that any contact at all with private antiquities holdings both validates the market and essentially lends our expertise to the increased commodification of cultural objects. I’m in camp two. I’ve built my career on a foundation of integrity and I am always surprised when folks think that my integrity is negotiable. I think that archaeologists and museum professionals who authenticate outside of set schemes and monitored conditions are forfeiting their integrity for little reward.

Here in Scotland, we actually have an interesting option for people bearing old stuff. Our national Treasure Trove Unit holds a series of outreach events each year. Many of these are Finds days throughout Scotland where members of the public are invited to bring artefacts that they have found to be identified and reported. Of course, all subsequent actions after this proceed in accordance with the law, and I have no idea what they’d do if someone plopped a Maya pot down on their table. But though this we get the benefit of educating members of the public about how to do things right without the drawbacks of skirting the law, propping up the trade, and forfeiting our integrity.