A new biography of the now-infamous art dealer, Hildebrand Gurlitt

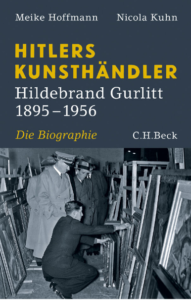

Hitler’s Art Dealer: Hildebrand Gurlitt, 1895 – 1956 (Hitlers Kunsthändler: Hildebrand Gurlitt)

By Meike Hoffmann and Nicola Kuhn

2016, C.H. Beck (German)

Review by Jens Notroff (Berlin)

With the so-called Schwabinger Kunstfund (‘Munich artworks discovery’) in 2012 and the media attention it got in the aftermath, a previously unknown art collection of considerable extent, including paintings by Monet, Renoir, Matisse, Marc, Chagall, Dix, Liebermann and many others suddenly appeared in the focus of public discussion. About 1,279 works of art were found in the apartment of a Cornelius Gurlitt in Schwabing (Munich), Germany, in the course of a tax evasion investigation. Where did this enormous collection actually came from – and who does it belong to?

With the so-called Schwabinger Kunstfund (‘Munich artworks discovery’) in 2012 and the media attention it got in the aftermath, a previously unknown art collection of considerable extent, including paintings by Monet, Renoir, Matisse, Marc, Chagall, Dix, Liebermann and many others suddenly appeared in the focus of public discussion. About 1,279 works of art were found in the apartment of a Cornelius Gurlitt in Schwabing (Munich), Germany, in the course of a tax evasion investigation. Where did this enormous collection actually came from – and who does it belong to?

To answer this question, one has to delve deep into Gurlitt’s family history. A family of artists, scholars, art historians, art collectors, and art dealers, and a history that reflects much of Germany’s own past condensed into the microcosm of a single lineage. The story of Hildebrand Gurlitt, Cornelius’ father, whose entanglement with the Third Reich and its oppressive expropriation politics holds the answer to many questions regarding the collection discovered in that apartment. This biography tells the story behind those paintings. A connection regarding the authors of Hitlers Kunsthändler: Art historian Meike Hoffmann is coordinator of the “Entartete Kunst” (degenerate art) research centre at Berlin’s Freie Universität, and the book (read: the reader) benefits from her long-term engagement with the case of Hildebrand Gurlitt. Hoffmann is also one of the first experts consulted to identify the paintings confiscated in the son’s apartment. Her co-author, Nicola Kuhn, is a well-known art critic and editor at a major Berlin newspaper.

In this book both authors paint the multi-faceted portrait of Hildebrand Gurlitt, a man on his way from advocate and patron of avant-garde art (personally acquainted with expressionists of the ‘Brücke’ group and others) to someone trying maintain his position under a dictatorial regime. It is also the biography of a man in the shadow of a family name, burdened with expectations to live up to (his father Cornelius, going by the same name as Hildebrand’s son, having been the founder of Baroque art historical research and a pioneer in monument and heritage preservation). But it is also a name which opens doors and generates opportunities at the beginning of his career. Hildebrand Gurlitt starts as head of Zwickau’s König-Albert-Museum (art collection) which soon becomes a focal point for the Modernist movement due to his tenure. This commitment to Modernism did not find much approval in a time of strengthening conservative influence, and subsequently cost him the position. Gurlitt was also forced to resign as managing director of Hamburg’s Kunstverein in 1933 after refusing to hoist the swastika over his museum for celebrations on the occasions of May 1st (having just become a legal holiday that very year) – opposing the system he later would cooperate with, and even utilise for his own profit. An emblematic trait of his character as Hoffmann and Kuhn put it: A critical mind turning opportunist.

The Hamburg art exhibition became famous for being the first one banned in the Third Reich; afterward Gurlitt tried to find a new path within the art market–oscillating between patronising modern art and profiting from it. But again he clashed with the political system – being considered a ‘quarter Jew’ according to the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws he was again threatened by an occupational ban … unless he could be of use to the Reich. Which he could, being the networked art connoisseur he was. This was a turning point, this was Gurlitt’s deal with the devil: he accepted the responsibility to procure foreign money for the Reich by acting as commercial agent in ‘degenerate art’. After the fall of France, he was sent there in 1941 to assume control over the local art market, successively extending his sphere of influence to Belgium, Holland, Hungary, etc. – joining an influential circle of privileged art distributers; Allied Forces would later rank him as ‘chief dealer’. And it is in the frame of this function that Gurlitt also seizes the opportunity to expand his own collection. During that time he established connections and relationships which still would be useful much later for his son whenever Cornelius (the younger) needed to sell a piece of the collection.

Analysing a large variety of known sources and offering new material as well, the authors succeed in presenting the distinct and fascinating biography of a man who is passionate for art (at one point he later would even offer paintings by his grandfather Louis, a landscape painter, as compensation for confiscated ‘degenerate’ works to the Hamburger Kunsthalle) but struggles when making accommodations with a political regime of the worst kind that also work to his own advantage (which, admittedly, may be all too easily judged from the perspective of a generation who has seen how all this ended). However, it cannot and should not be veiled that Hildebrand Gurlitt did, knowingly, profit at the expanses of others (Jews under threat in particular) by obtaining art at way under its value. And this is where the book also closes the circle to the ‚Schwabinger Kunstfund’ again and which makes this volume so valuable in terms of the current discussion on art crime, provenance research, and restitution.

While it is true that Gurlitt did support and even cooperated with the institutional restitution of looted and ill-gotten art, he also blocked requests by individuals and their heirs – as far as boldly lying about the whereabouts of certain paintings (in his private collection) upon direct questioning. However, a crucial insight of Hoffmann’s and Kuhn’s book “Hitlers Kunsthändler” is the notion that a large part of the collection discovered in that apartment in 2012 was (according to current state of research) apparently not looted (five of the paintings, however, could have been identified as such by the newly created task force), but inherited or bought (under which circumstances is a different matter). Eventually, Gurlitt has to put up with being judged by history. Even if this rather should mean a more moral than a legal judgement.

The book is result of and reference to an enormous amount of research and it certainly is a true repository for anyone looking into instrumentalisation and entrapment of art and the art market into the Third Reich’s politics. There are so many data and research results packed into this volume that sometimes its narrative seems to lose the course it set in the prelude; occasionally the reader may feel overwhelmed by the abundance of information hailing down. Yet in the end none of this knowledge seems redundant or futile. I learned for instance, admittedly to my surprise, that Goebbels and the Nazi government tried to claim the avant-garde art (expressionism in particular) as specific ‘state art’ of the ‘new Germany’ right after seizing power in 1933; only later, once artists took a stand against the regime, was modern art defamed as ‘degenerated’. Yet it is in particular the book’s last chapter on “Consequences for public museums and private collections” that, addressing the issues of restitution and politics in the face of necessarily revised bills, and a plea for provenance research, invites a much larger discussion on these issues. And if only to get a better understanding for the interrelation of those complex circumstances, Hoffmann’s and Kuhn’s book is a gainful source to comprehend the complicated situation of art ownership and possession (which are not necessarily identical) in consequence of the Third Reich’s politics of expropriation.