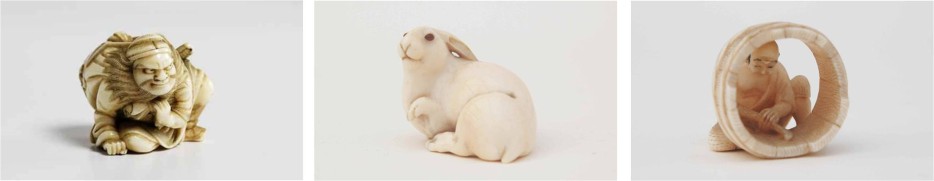

Tiny Japanese sculptures are silent witness to an art florescence then catastrophe for Jewish families under Nazism.

The Har e with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance by Edmund de Waal

e with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance by Edmund de Waal

2010, Chatto & Windus

The great thing about reading ever so slightly older books is that you can get them on the cheap. When students in my free online art crime course mentioned books that I had somehow missed, I was able to pick up paperback copies at 99p a pop. The Hare with the Amber Eyes came out during the darker days of writing up my PhD, I wasn’t reading anything else but Bolivian laws and turn of-the-century Peruvian political writings which equated the Inka governance model with socialism and modern Indigenous people as the ideal proletariat. I didn’t have time for a moving, beautifully written story about art, objects, memory, family, and loss.

But now I do! Let the review begin!

The Hare with Amber Eyes is less about object and more about context. Changing contexts. With the death of his great uncle, author Edmund De Waal inherits 264 netsuke: tiny carved sculptural pieces which would have once been used to attach a separate pocket to kimono. The collection of netsuke travel from Japan to Paris, Paris to Vienna, back to Japan after the second world war, and eventually to the home of the author in London. The story is deeply personal, the author is himself a character in the story, traveling to reveal a family history, but it also provides a much broader picture of place and transition. Of art, exoticism, learning, literature, and change through beautiful then turbulent times. The netsuke sit in their vitrine, quiet witness to the changes around them, sucking it all in to their provenance. Their history.

We readers are transported to late 19th century Paris and dropped in the middle of a storm of money and art. We’re with Charles Ephrussi, the author’s great grandfather’s cousin. Who is Charles Ephrussi? Well Swann apparently! He is one of two inspirations for Proust’s Gilberte Swann in À la recherche du temps perdu. He’s also the fella in the back with a top hat in Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party. A member of an extremely wealthy banking and business family who had come to Paris from Russia, Charles was part of the highest echelons of the Paris art world (collected it, wrote about it, paid for it). He was also Jewish which brought with it the casual racism and the overt anti-semitism; don’t forget some of your favourite French artists at the time were horrible, horrible racists. Charles died during the Dreyfus affair, I’m sure all that didn’t help his weak heart.

Now forget all the spectacular, famous, valuable art that you rightly have already assumed that Charles Ephrussi collected. Let’s think small. Responding to a fad for Japan that swept the European arty set in the late 19th century, Charles began to collect netsuke amassing a respectable collection of them. Want to picture Manet, Renoir, Proust, etc picking up the little hare with amber eyes, rolling it around in their hands, and setting it back down again? Go ahead. Very likely happened. As time passes the netsuke, still lovely and curious, move out of Charles’ primary art focus. In 1899 Charles gifts the netsuke collection to his cousin in Vienna, Viktor von Ephrussi, as a wedding present. Viktor is the author’s great grandfather.

In Vienna the netsuke move into the Palais Ephrussi, where they had a more intimate existence deep within the household. In Vienna, the netsuke lived in a vitrine in the dressing room of Emmy Schey von Koromla, the author’s great grandmother. There, as she dressed, her three children (and then a fourth much later) were allowed to play with the tiny animals and people. When dressing was over, they went back into their vitrine. De Waal portrays this as a beautiful, tender family ritual that sits in contrast to what was going on outside. A devastating first world war. Rising anti-semitism. The advance of the Nazis. The Anschluss.

You know what is going to happen to a wealthy Jewish banking family with a house filled with art.

Viktor and his youngest son are arrested and threatened with being sent to Dachau until they agree to sign away ownership of Palais Ephrussi, all of the art within it, and especially all of the rare and valuable books in their extensive library. As usual, the Nazis weren’t willing to just take the items, they wanted legal-seeming paperwork. The children scatter to other countries for safety; Emmy dies (the author implies by suicide); the elderly Viktor escapes with nothing to Czechoslovakia then the UK; and the war ends. Elisabeth de Waal, a lawyer who is the child of Viktor and Emmy and the grandmother of the author, travels back to Vienna to see what is left. The answer is almost nothing. But the netsuke are there. The family’s former maid had hidden them in a mattress. Elisabeth brings very little back with her to the UK, but she brings the netsuke. Tiny little pieces of memory, symbolic of the greatest of losses.

Plot twist, the netsuke go to Japan next! The family decides that Ignace Ephrussi, Elisabeth’s brother and the author’s uncle, should have the collection and in 1947 he moves to post-war Japan and never leaves. He falls in love with a man named Jiro Sugiyama, they travel the world together, and the netsuke live in a display case in the connected apartments that they share. A true love story between a Viennese Jewish veteran and a Japanese man set against the backdrop of post-war Japan is a book that I would buy the heck out of, but we aren’t here so much for Jiro and Iggy. In Japan the netsuke are studied, published, and praised. Their layered contexts perhaps being missed by most viewers who would experience them as Japanese, without a thought to Proust or Manet touching them, or Hitler parading by outside their window. There the netsuke were, doing their netsuke thing.

And now they are with the author, Edmund de Waal. They came back to Europe with him after his uncle’s death.

I’d be remiss if I did not praise the author’s provenance research. De Waal traces every move of the netsuke from the moment they leave Japan (for the first time) in the late 1800s, usually with various types of supporting documentation that is mentioned in the book and presumably with other documents not presented. Objects have histories that are discoverable and documented. Objects that are presented with no history should be rejected. Looted antiquities and stolen art appears on the market because so many people accept a false premise that there are no records of anything. There are: both for masterpieces and for a collection of tiny little ivory netsuke that children played with while their mother was getting dressed.

I’d be remiss if I did not praise the author’s provenance research. De Waal traces every move of the netsuke from the moment they leave Japan (for the first time) in the late 1800s, usually with various types of supporting documentation that is mentioned in the book and presumably with other documents not presented. Objects have histories that are discoverable and documented. Objects that are presented with no history should be rejected. Looted antiquities and stolen art appears on the market because so many people accept a false premise that there are no records of anything. There are: both for masterpieces and for a collection of tiny little ivory netsuke that children played with while their mother was getting dressed.

Art buyers: Hire. Provenance. Researchers. Don’t buy anything that hasn’t been properly provenanced by a professional who doesn’t profit from you buying the piece. For relatively little money, you get peace of mind and compelling stories.

You should absolutely grab a copy of The Hare with Amber Eyes. It’s filled with little gifts: surprising facts (Donna at the pub: “Wait, what?! Charles is Swann?!”) and useful observations. De Waal, himself, is a ceramicist whose careful approach to history betrays his own artist’s eye. It’s delightful and I was sorry it was over. Then again, it’s not. The netsuke are now silent witness again, this time to a successful book. What is next for them?