This book will ruin you. You MUST read it.

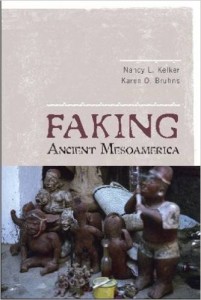

Faking Ancient Mesoamerica by Nancy L. Kelker and Karen O. Bruhns

Faking Ancient Mesoamerica by Nancy L. Kelker and Karen O. Bruhns

2010, Walnut Creek

When I first read Faking Ancient Mesoamerica and its sister book Faking the Ancient Andes (201o) I freaked out. My eyes got wider and wider with each turn of the page. At some point my jaw dropped and never closed again. I had worked on or in either Mesoamerican or Andean archaeology for over a decade, I had a few degrees focused on illicit antiquities from those regions, and I sure as heck thought I had been around the block a few times and knew what was what. I really didn’t. Not when it came to faking. Faking Ancient Mesoamerica shattered so many of my closely-held illusions about our corpus of (so-called) ancient American art that when it was over I actually had to sit and take stock of what I was left with.

Could I believe anything anymore?

An ‘unprovenanced’ antiquity on the art market is almost certainly one of two things: looted or fake. If you aren’t buying the pathetic and tattered spoils of neo-colonial subjection, you are buying a knock-off. Preservation advocates are often tempted to say that fakes on the market are a good thing and that, perhaps, ‘we’ should flood the market with fakes as they punish buyers who are willing to otherwise buy illicit antiquities. However, as we saw in Shaky Ground by Elizabeth Marlow, fakes are dangerous. They pollute the corpus of knowledge about ancient cultures as we experts even often are unable to definitively say which objects are real and which are not. Let me be clear: fakes only exist because there is a market for looted antiquities. If there was no market for looted antiquities and we only were dealing with artefacts dug up during the course of real archaeology, there would be no issue. But, alas, no dice. It is all a big mess and the reality is that we can’t really sort the mess out.

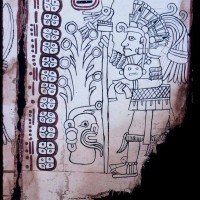

But Kelker and Bruhns give a brave try at it. In Faking Ancient Mesoamerica, the authors sweep through the broad categories of ancient stuff (and ancient fakes) that have been known to appear: ceramics, stone, books, etc. They provide careful but concise explanations about why such material is fake-able, what the market motivation is/might be for such fakes, how the fakes have been detected, and present a few shocking case studies. Sometimes they outright say that a well-known ‘antiquity’ is a fake. Other times they accurately portray our painful lingering uncertainty. Sometimes they name names. Other times they leave it unsaid…but, come on, we all know who they mean.

The authors push and prove the thesis that ‘old collection’ doesn’t mean ‘authenticity’ on the Mesoamerican antiquities market. And good on them for that as this is something I see all the time in antiquities sales: the assertion that because a piece of central Mexican pottery has been in an anonymous Swiss collection since 1920, it is much more likely to be real, as if somehow the recent past were simpler and sincere times when folks were too dull to make a buck off the back of art market gullibility. Oh heck no! Via notes from contemporary experts, photographs, and just the general audacity of some of the early junk that people collected, Kelker and Bruhns push large scale Mesoamerican faking well into the 19th century. Old fakes are just as fake as new fakes.

By the way, thanks to Faking Ancient Mesoamerica, I tracked down and scanned Leopoldo Batres’ 1910 book about Mexican artifact forgery. It is available here.

I often ask myself why it is so hard for us to believe in fakes on the antiquities market or, rather, to accept the volume of fakes that are out there. The headlines are all “[Insert someone scary] are looting all of the archaeological sites and making bazillions on the antiquities”; they are never “Locals realise it is way easier to fake antiquities than dig them up and that the people they are selling them on to don’t know the difference”, even when the second is well supported by what little evidence we have. Why would anyone toil in the hot sun for hours, days, and months without guarantee of finding anything at all when they could just make that stuff up?[1]

What I think and what Kelker and Bruhns seem to support is that it is hard for us to believe that antiquities are fakes because we really, really don’t want to. They argue that antiquities forgers purposefully create fakes that are meant to appeal directly to what the contemporary public wants. They are the right kind of sexy, exotic, or beautiful for the moment they sold in. They confirm our notion of what ancient art should be, rather than what it is, and it meets all of our pre-existing expectations. Thus the fakes are so believable because they give us what we want. We have trouble seeing their often obvious flaws because we are in love with whatever it is that they represent.

And, because of that, I should say that Faking Ancient Mesoamerica has not been accepted in all circles. Some folks, mainly within the market but also in academia, say that Kelker and Bruhns’ fake denunciations have gone too far and argue either for the authenticity of certain pieces or a sort of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ approach. In other words, the authors have seriously challenged these peoples’ closely-held beliefs about ancient art and, well, about reality. People don’t like it when their reality is questioned.

I do. I like that a lot, but many don’t.

Anyhow, because in most cases you can’t actually know if an unprovenanced antiquity is real or fake I suggest that you use this book as a tool for forming your own opinions. Don’t automatically believe anyone about authenticity unless the piece came out of the ground during real archaeology. Don’t blindly believe the museum. Don’t blindly believe an expert. Definitely don’t blindly believe a dealer. And, in the end, don’t blindly believe the authors of this book. They don’t want you to just take their word for it anyway, they want you to look for yourself and develop your own critical eye.

I can safely say that this book entirely changed how I view Mesoamerican museum collections.[2] I have never looked at them the same way again. It upped my previously-mentioned critical eye significantly and although I may have lost my ignorant bliss about the extent of Mesoamerican artefact fakery, I didn’t want the ignorance anyway. I love the ancient cultures of Central America and acceptance of fakes as real harms my understanding of those cultures.

I couldn’t afford NOT to read this book. You can’t afford NOT to ether.

—

[1] Good gosh, you could ask this about archaeology. I am now freaking myself out thinking about how much archaeological research might just be made up crap done by a lazy archaeologist. Yikes.

[2] And because of this I cite the heck out of it all the time and assign it to my students.