Years of library and archive theft go unnoticed at a University; despair for our print collections.

Disappearing Ink: The Insider, the FBI, and the looting of the Kenyon College Library by Travis McDade

2015, Diversion Books

Oh coincidences, so easy to interpret as significant. Time and time again I find my day-to-day life linked in some way to the books I am reading. It’s our human ability to detect patterns, usually so valuable for things like ‘not eating poisonous berries’ and ‘not going in the type of cave where the scary bears live’, playing tricks on us. It’s called apophenia, ‘the human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns within random data’. Logically I know this but I still marvel a bit.

Oh coincidences, so easy to interpret as significant. Time and time again I find my day-to-day life linked in some way to the books I am reading. It’s our human ability to detect patterns, usually so valuable for things like ‘not eating poisonous berries’ and ‘not going in the type of cave where the scary bears live’, playing tricks on us. It’s called apophenia, ‘the human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns within random data’. Logically I know this but I still marvel a bit.

That means that I am pretty impressed when I find myself reading a book about university library book theft on the same day that I am able to convince my own university library to let me take a ‘consult in library only’ book out of their building and into mine for a few hours. No, I didn’t steal the book. Yes, I returned it promptly and in one piece. Still, I was able to negotiate a situation where the rules were bent because of my trustworthiness.

Above anything else I see Disappearing Ink by Travis McDade as a book about how security breaks down in the face of, well, misinterpretation of patterns and poorly placed trust. The best library, archive, and museum security system in the world will fail when everyone gets used to a trusted individual repeatedly violating it.

I was drawn to Disappearing Ink initially because a small part of it is a bit close to home. The story opens with a librarian at Georgia College and State University bidding on a Flannery O’Connor letter on eBay. The librarian is pretty jazzed. GCSU is in Milledgeville, Georgia, same town as O’Connor’s ancestral home. Same town she died in. Close, incidentally, to where I am from… at least by Georgia standards. The letter is a big find but something feels wrong; the librarian thinks he has seen the letter before. Sure enough he has. It was meant to be in the library archives at Kenyon College, Ohio. Kenyon also thinks the letter is in their archives. Uh oh.

‘Wait,’ said I, ‘A book about book and document theft where the crime unravels around the discovery of Georgia Southern Gothic loot? I’m in.’

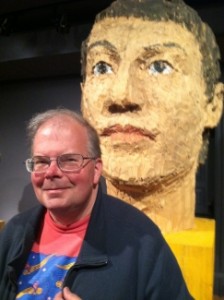

In this short book, McDade takes the reader through the case of David Breithaupt, a beat-writer-obsessed part-time night librarian at Kenyon’s Olin Library. For years, Breithaupt removed items from the library and, with the help of his partner, sold them first to dealers in person then online. He went through the stacks, the special collections, then the paper/correspondence archives. He stole and sold hundreds of items, maybe more. No one noticed until the Flannery O’Connor letter.

The security failure at Kenyon is fascinating. Breithaupt’s crimes were facilitated by the Olin Library’s poor security. At a time when key pads and swipe cards were standard elsewhere, Kenyon depended on physical keys for access restriction. Keys that, of course, could be borrowed or copied. Keys that didn’t record WHO entered a door. Keys that were not very well monitored.

For a long time Breithaupt had all the key access he needed to steal significant books, despite not having a job that required special collection access. He simply walked in at night when no one else was around and took stuff. Even after an exercise in security tightening where some keys were taken away from staff, including Breithaupt’s special collections key, he was still able to gain entry to the supposedly secure room. This is where pattern misinterpretation and trust come in. To get into the collection Breithaupt would chat up cleaning or security staff at night, tell them he had to do something or other legitimate in the special collections room, and they would let him in. He did it often enough that some of the grounds staff interpreted it as normal.

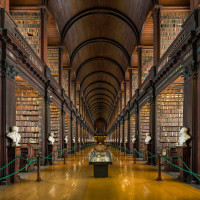

I wonder why libraries are so low on our list when it comes to cultural security and protection. I wonder if, deep down, we still don’t conceive of libraries as museums or preservation bodies. Rather we inevitably identify them with lending, with daily use, with items in motion and flux. I wonder (library people can tell me) if that is how we fund them as well. Are we giving staff high end security training? Are we providing these institutions with staff to monitor and inventory collections for theft?

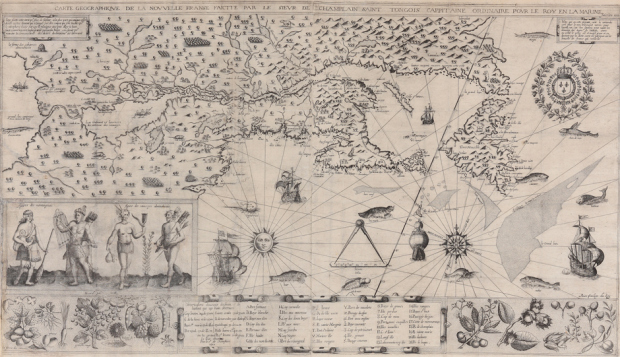

Take, for instance, the Boston Public Library, a beautiful institution which, for years, loaned me VCR tapes during times of student poverty and got me into the DAR following a long weekend and a bet made during a West Wing marathon. It’s the second largest public library after the Library of Congress and it has stuff, to put it mildly. Lots of stuff that it has to protect. From books on the stacks to a whole hall of neo-Egyptian/neo-Assyrian/neo-Biblical John Singer Sargent murals. They have a lot to deal with. The hot news this week was that the library recovered a 1612 map compiled by Samuel de Champlain which was stolen from the library in 2003, seemingly by E. Forbes Smiley, who confessed to stealing 34 maps from the BPL (but not this one), and 97 maps from various libraries total. The BPL is still missing 68 maps and they suspect Smiley for most of those thefts. So, great, they recovered one of 69 missing maps, but it is terrifying that as late as 2003, fella was able to rip the place off so monumentally.

Perhaps the most devastating line from the Boston Globe’s report on the Champlain map recovery: “The Boston Public Library has a digital image of only one of the remaining 34 maps that are missing”, meaning the ones that Smiley confessed to taking. In other words, they have no proof that any map that surfaces is THEIR map. In other, other words, their security was lax and they didn’t do the minimal recording required for post-theft recovery. How are things now? The BPL “has digitized more than 8,000 of its rare maps as part of a project aimed at digitizing about 20,000 maps”. So 12,000 maps, the majority of their collection, do not have the minimal documentation needed to effect return if they are stolen. Even if a stolen map is recovered, without a photo the BPL may not be able to prove it is theirs. Not. Cool.

At this point anyone reading this who is involved in protecting a collection should be worried. Does your security need review? Are rules bendable? Is access lendable? Take a moment.

However much he would like to argue otherwise, Breithaupt’s guilt is not in question here. Fella robbed the heck out of Kenyon and made up laughable lies in an attempt to cover himself. He was sued and was prosecuted. He lost and pleaded guilty. But the bigger story is library security or lack thereof. Book and document theft is lucrative; people are going to do it. Read it here: there are some hot criminology PhDs waiting to be done on this topic.

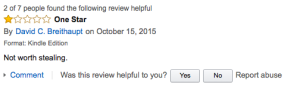

Back to Disappearing Ink: I found it a worthwhile and easy read. I read it on an overnight transatlantic flight (I can’t sleep on planes), and the writing was light enough and the story clear enough for super sleepy me to follow. To make matters more exciting, certainly one and possibly four of the book’s negative Amazon reviews are from David Breithaupt himself! He totally couldn’t leave it alone. Well, one is from him, the rest seem to be from friends. If it riled them all up, it’s worth your time.