*The* book about the build up and discovery of the Gurlitt art hoard.

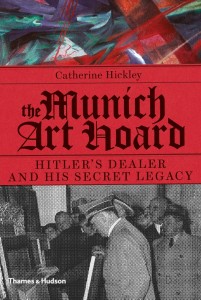

The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy by Catherine Hickley

2015, Thames & Hudson

Yes! This! This is the Gurlitt book I wanted. If you are going to buy a Gurlitt book, this is the one.

Yes! This! This is the Gurlitt book I wanted. If you are going to buy a Gurlitt book, this is the one.

Some of you may recall that a few weeks ago I reviewed a book about the German art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt and I really didn’t like it. I wanted to like it because I need something about the spectacular recent discovery of all that art, some of it the product of Nazi forced sales etc., to bring to my students, but it was not good. Thankfully author Catherine Hickley has come to my rescue. The Munich Art Hoard is well, researched, engaging, and useful.

It is also high quality. Like, seriously, physically high quality. The paper that it is printed on is so thick that, as I read, I kept thinking that I had two pages stuck together. Nice paper? I’m impressed.

Hickley starts her book by telling about the tragic Holocaust experience of David Toren who lost his family to the Nazis, not to mention his uncle David Friedmann’s significant art collection with particular focus on the 1901 painting Two Riders on the Beach by Max Liebermann. The last time Toren saw the painting was just after Kristallnacht and just after his dad had been hauled to then let out of Buchenwald. Yow. By opening with the story of a heir, the author is able to tie the loss of art to the loss of, well, everything. Loss of family, loss of lives. It humanizes restitution and return, and sets up the framework of the story.

And the story is fascinating. Hildebrand Gurlitt, a Dresdener son of an artistic family, is drummed out of the museum world for his support of modern art (and perhaps his Jewish grandparent) and ends up an art buyer for German museum collections under Hitler. He makes smart trades, amasses a fortune, and stashes away a significant collection of so-called “degenerate art” pieces. After the war, when the Monuments Men come calling, Gurlitt says his records were destroyed in the bombing of Dresden, the start of years of lies concerning the whereabouts of certain significant pieces of art, art that was in his home all along.

After Hildebrand Gurlitt’s death, his collection passed to his wife and then to his two children, particularly to his son Cornelius. A hermit for more than half a century, Cornelius Gurlitt was a solitary man with some mental health issues. He spoke to next to no one but his sister and his doctor and seemingly lived off the money his father amassed during the war. At least near the end of his life he was convinced that there was a Nazi plot afoot to separate him from his fathers collection of art. Art that nearly no one knew he had until a trip across the boarder, a perhaps-dodgy tax investigation, and a few other twists and turns exposed the Gurlitt art hoard to the world.

Suddenly, there was the missing Two Riders on the Beach and who knows WHAT else. There was a LOT of art in the Gurlitt residences.

The author is quite good at capturing the strange and subtle aspects of Hildebrand Gurlitt’s position during the Nazi era. She denounces that headlines that called him a “Nazi art dealer” as he was most certainly not a Nazi. As a quarter Jew he was treated as suspect, barred from certain jobs, and certainly barred from joining the Nazi party. Indeed the elder Gurlitt was an anti Nazi but, as the author points out, a combination of fear and ambition caused him to compromise these beliefs and he grew rich by doing so. This is an important distinction to make. It doesn’t absolve Gurlitt of any crimes, and he certainly committed crimes, but it shows the complexity of the war time art market and the people engaging with it. Interesting.

Speaking of interesting: Chapter 8, Selling Plunder. This is a nearly self-contained piece about the challenges and frustrations of dealing with German art law specifically and the return of stolen cultural property more general. It is a complicated topic, but Hickley does a great job of summarising the legal twists and barriers without becoming over technical or bogged down with details. I liked this chapter so much that I may make it assigned reading for my masters students. I also may contact the author about adapting or excerpting it for use on my free online course. Maybe!

I’ll say it again, if you are going to get a book on the Gurlitt hoard, get this one. This is a timely book and we best all get our head around who the Gurlitts were as we will be thinking about them for years to come. The Munich Art Hoard a good foundation for understanding the case and whatever happens with it over the next few years.