Posted on 2 October 2012

Guatemala has been the site of many of my most vivid dreams and imaginings. When I was 19 years old, I spent a summer living in a run down building in Roxbury, working part time, and spending the rest of my days sneaking into Harvard’s Tozzer Library and reading archaeological accounts of Guatemala from the first half of the 20th century. I remember feeling that it was imperative that I know the information in those texts: I had decided that I was going to focus my degree on Maya archaeology. The semester before I had taken a course called Maya Cities taught by Norman Hammond and was scheduled to take another course on Central and South American art history taught by Clemency Coggins the next term. There was word that I would be working on projects in Belize then Guatemala. I remember feeling this sense of urgency, that I was behind, that I had to suck up the textual artefacts of a century of Maya archaeology. That I couldn’t conduct Maya archaeology unless I did. At Harvard I read what I couldn’t access anywhere else. It was all incredibly nerdy.

That experience has left me with an odd amount of difficult-to-apply knowledge of earlier Maya archaeology (which, at the present, has an outlet in the Trafficking Culture Website, as well as a chapter that I wrote for an upcoming British Academy monograph entitled Publication as Preservation at a Remote Maya Site in the Early Twentieth Century). Clearly I have mostly migrated south, but in the back of my mind I still play with the idea of getting involved in Guatemala again in some way. Ideas? Whatever else, I follow Guatemala closely.

I’m happy to say that the US/Guatemala Cultural Property MOU has been extended for another five years as of Friday. As Rick St. Hilaire pointed out in a recent post, the import ban now includes “certain ecclesiastical ethnological materials dating to the Conquest and Colonial Periods of Guatemala”. FINALLY! While these two new categories might contain a number of things, what we are clearly talking about are church loot and masks. These things are hot right now, but I wonder if they are hot in slightly different circles than, say, your Maya pot. They are collected for sure but they seem to enter into the décor market. That is not to say that antiquities are not used to decorate, but to me a Guatemalan conquest-era mask reaches a market that is more like that of decapitated Buddha heads. The ecclesiastical art certainly is purchased by someone else. Auction catalogues and dealers classify them separately. I wonder if we cultural property research folks do as well to the point of sort of ignoring them?

The Guatemala MOU is not the only one that covers, well, church stuff and masks. “Ecclesiastical Ethnological Materials” are barred from import from Colombia as are “Colonial Ethnological Objects” (which mostly means Church stuff) from Peru. “Colonial and Republican” objects are restricted under the Bolivia MOU too, a category that includes church stuff, masks and costumes, and, of course, your post-Conquest textiles.

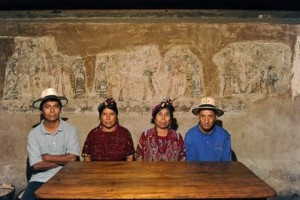

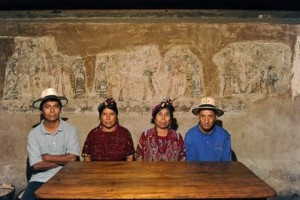

Guatemala seems an obvious candidate for the protection of Conquest-era objects. The stuff is beautiful, the ‘sites’ are remote, and the property is in demand. Heck we know so little about Conquest and post-Conquest culture that this may represent another point where the market beats archaeologists to the punch. Everything is a surprise when it comes to the Conquest and immediate post-Conquest. Take, for example, the murals recently found in the kitchen of a house in the village of Chajul:

The paintings depict figures in procession, wearing a mix of traditional Maya and Spanish garb. Some may be holding human hearts.

Or those may be masks in their hands. They also have costumes on…and Chajul is mentioned in the Rabinal Achí, perhaps the only bit of pre-Conquest Maya drama to survive which is now part of our certified World Intangible Heritage. You best believe I read some shoddy translations of the Rabinal Achi while sitting in the Tozzer Library years ago. I drooled on my desk when I heard about these. We don’t know what is going on there! Golly I’m glad that they didn’t get torn down and trafficked. Something like 80% of the people of Chajul live below the poverty line and the civil war hit that area super hard. Buy their cooperatively grown coffee.

Those murals represent exactly the sort of amazing Conquest-era material heritage that is just starting to come to light in Guatemala. The masks, the ecclesiastical pieces that combine the Indigenous with the foreign and so on are so strongly tied not just to ancient but to very modern Guatemalan identity that it baffles me that we illicit antiquities folks rarely talk about them.

|

As the Ramirez family of Chajul found out, if your home is

over 300 years old, you find strange stuff in the walls. |

It may just be the archaeological nature of a lot of this kind of work: historical archaeology occupies an odd place in our discipline, which is unfair. Historical archaeology in Latin America barely exists. I will say that what little historical archaeology that IS being done in Central and South America is about the coolest stuff that I get to read.

So three cheers for Guatemala’s masks and church stuff! I’ll be writing a bit more about church looting in Bolivia quite soon, no doubt, so stay tuned!