As submitted to the US State Department’s Cultural Property Advisory Committee.

[Photo by Snow Winters, 2005]

There are only a few days left for you to voice your support for restricting the import of looted and stolen Bolivian art and antiquities into the United States. The US State Department is calling on everyone, from experts to interested members of the public, to comment on this important international agreement. I beg you to consider uploading your thoughts. ANYONE can comment but you have to do so on or before 9 May.

I’ve posted full instructions on how to do so here.

I uploaded my comments to the US Government website today but as it takes a bit of time for them to show, I will share the letter here. You can also download a PDF of it.

Yes mine is a bit in-depth but Bolivian heritage is exactly what I study. That should not discourage you. Your own feelings, particularly concerning points 3 and 4, should be heard. If you love the past, please write in support of preserving it.

Dear members of The Cultural Property Advisory Committee,

I am writing to you to express my support for the proposed extension of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Bolivia Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material from the Pre-Columbian Cultures and Certain Ethnological Material from the Colonial and Republican Periods of Bolivia. The MOU remains our most significant tool for reducing the trafficking of stolen Bolivian cultural property into the United States. Although Bolivia has taken extensive measures to document and secure their heritage, the reality is that US market demand for Bolivian cultural property remains high. The removal of these import restrictions would lead to an increase in criminal trafficking between Bolivia at the United States; surely it is in the best interest of all parties to extend international partnership rather than invite criminality.

I am writing to you to express my support for the proposed extension of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Bolivia Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material from the Pre-Columbian Cultures and Certain Ethnological Material from the Colonial and Republican Periods of Bolivia. The MOU remains our most significant tool for reducing the trafficking of stolen Bolivian cultural property into the United States. Although Bolivia has taken extensive measures to document and secure their heritage, the reality is that US market demand for Bolivian cultural property remains high. The removal of these import restrictions would lead to an increase in criminal trafficking between Bolivia at the United States; surely it is in the best interest of all parties to extend international partnership rather than invite criminality.

Although I plan on attending the 24 May 2016 public meeting concerning the MOU, and will present an abbreviated statement at that time, I am in a position to offer here applicable information about Bolivia’s current cultural heritage policy and practice. Since 2004 I have conduced archaeological, anthropological, and criminalogical research in Bolivia, particularly focused on cultural property, law, and trafficking. A component of my doctoral research included a complete analysis of Bolivian cultural property law and policy since 1906, the year that the state laid legal and legitimate claim to all heritage objects, both discovered and undiscovered, within its territory. In 2012 I was awarded a three-year fellowship to conduct antiquities trafficking research in Latin America with Bolivia as a starting point and in 2013 I was awarded a Core Fulbright Award to fund fieldwork in Bolivia specifically to look at the on-the-ground effectiveness of policy such as the MOU in question. Results of my analysis have been published in peer reviewed academic publications (see “Additional Resources”). Now as lecturer at the University of Glasgow, Bolivian cultural property remains at the core of my research agenda.

In particular, I will focus on information related to matters referred to in 19 U.S.C. 2602(a)(1). I would be happy to provide supporting documentation for the information that I present and am available for further comment on these and other subjects related to Bolivian policy and cultural property. I note that my fieldwork in Bolivia ended in 2013 and there have been some changes to heritage management in the country since then. While I cannot comment specifically about the effectiveness of these changes, accounts from colleagues indicate that these have been improvements to the overall structure of heritage policy in the country and should be seen as positive.

(1) The cultural patrimony of the State Party [i.e., Bolivia] is in jeopardy from pillage of its archaeological or ethnological materials;

In late 2012 I conducted a survey of South American Colonial and Republican sacred art available for sale online via established art dealerships. I have since repeated this survey annually in December. It is clear from this survey that Bolivian objects covered by the MOU (e.g. ecclesiastical silver, colonial paintings) command high prices, experience a strong rate of turnover from year to year which I interpret as evidence of sale, and are offered with little information about their provenance. Moreover, the majority of art dealerships offering this type of Bolivian object are located within the United States. This clear market demand corresponds with a startling wave of cultural property theft from Bolivian churches: a practice that is recordable throughout the 1990s but saw an increase into the 2000s with several extremely significant thefts occurring in the period from 2011 through 2013. The profile of Bolivian objects for sale online matches the profile of objects stolen from Bolivian churches in the past 10 years. Several objects recorded during my online survey and located in the United States have been definitively shown to have been stolen from a particular Bolivian church (authorities in both countries are now aware of this). The connection between Bolivian church theft and the US art market is also demonstrable from several recent seizures and returns. It is clear that Colonial and Republican items in Bolivia are in significant jeopardy from pillage and that the United States is a major market for these items.

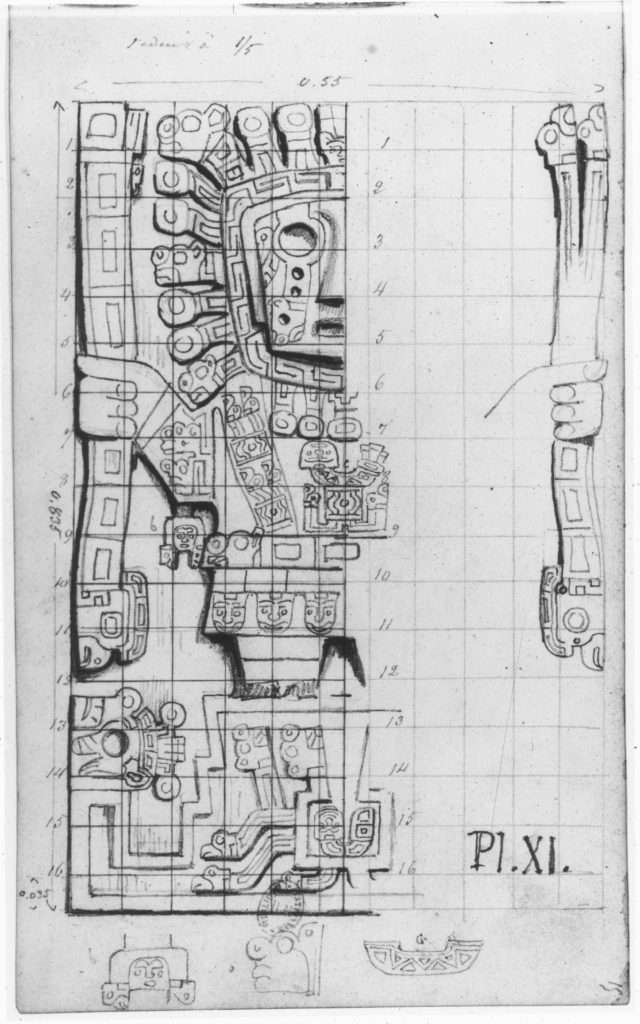

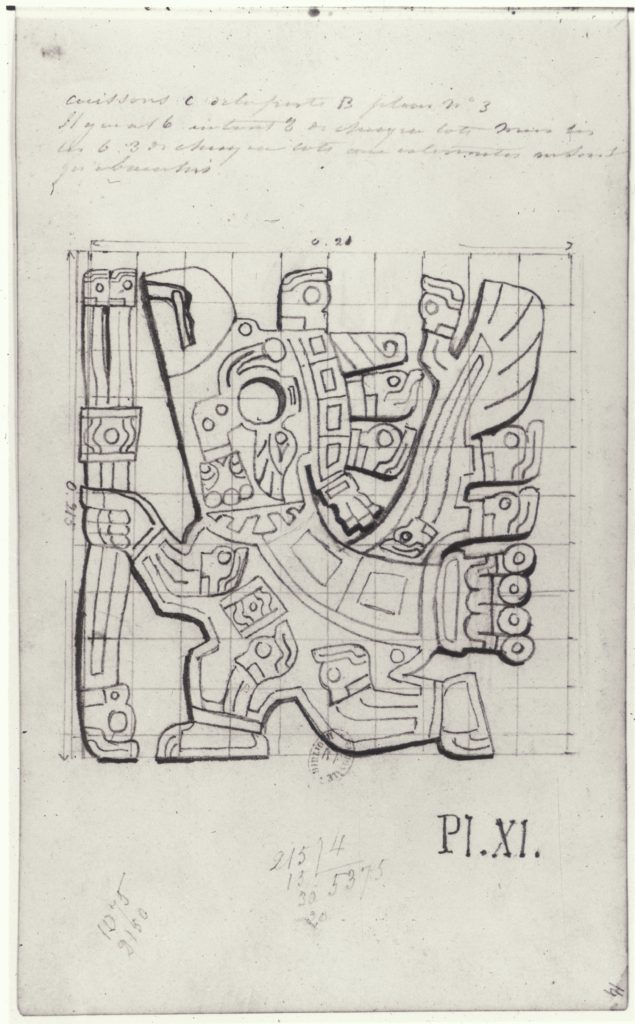

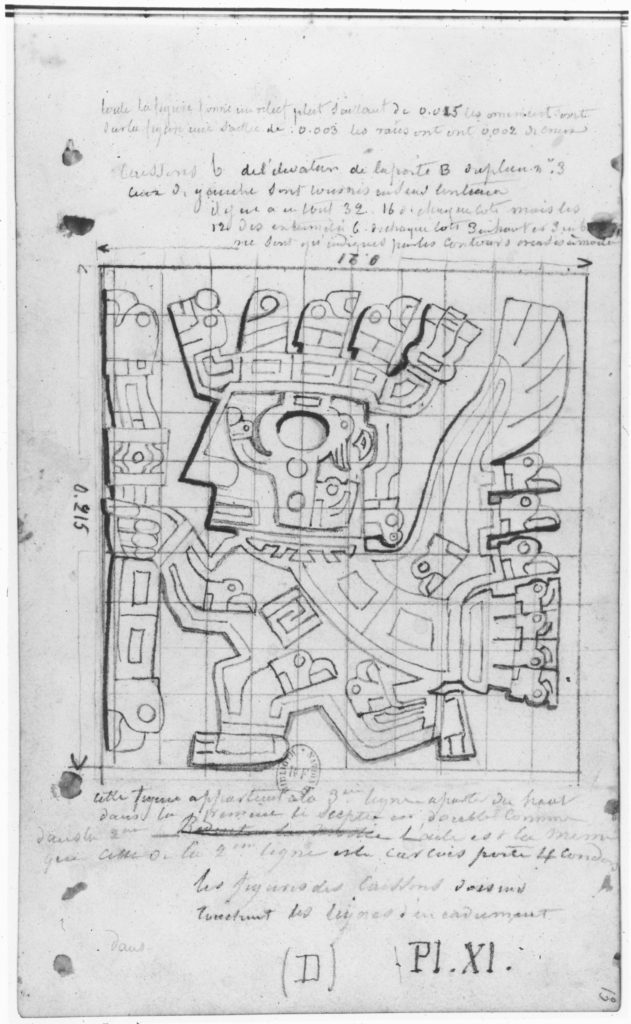

Although archaeological items have not been the primary focus of my recent research in Bolivia, there is indication that they too remain at risk of pillage. Of immediate concern is an increase in demand for items related to the Wari culture. Wari’s current market popularity appears to relate to several recent high-profile museum exhibitions in the United States as well as recent spectacular archaeological discoveries. Although the Wari were primarily located in what is now Peru, their “sister” culture, the Tiwanaku, were based in Bolivia during what has been termed the Andean Middle Horizon. Similarities in iconography and a known but undefined connection between the two cultures may mean that Tiwanaku material has increased in market popularity as well. This may also increase the risk that Tiwanaku material is being ‘passed off’ as Wari on the market. Accepting that market demand causes a supply to be found, this very recent increased demand for Middle Horizon artifacts places Bolivia’s sites at continued risk of pillage.

(2) the State Party has taken measures consistent with the Convention to protect its cultural patrimony;

Bolivia has had strong and clear heritage protection legislation in place since 1906. From the very start, Bolivian policy was clear about state ownership of all heritage, total prohibition of all digging without state-issued permits, and a ban on export abroad. Violations of these laws lead to adequate punishment under Bolivia’s penal code, and any crime involving the looting, trafficking, and destruction of heritage is considered aggravated. There is no legal way to buy, sell, or export Bolivian cultural property and there hasn’t been since 1906; it is all owned by the state and the state does not, as a rule, transfer ownership.

Bolivia has had strong and clear heritage protection legislation in place since 1906. From the very start, Bolivian policy was clear about state ownership of all heritage, total prohibition of all digging without state-issued permits, and a ban on export abroad. Violations of these laws lead to adequate punishment under Bolivia’s penal code, and any crime involving the looting, trafficking, and destruction of heritage is considered aggravated. There is no legal way to buy, sell, or export Bolivian cultural property and there hasn’t been since 1906; it is all owned by the state and the state does not, as a rule, transfer ownership.

The primary issue that Bolivia faces is enforcement of this set of laws and policies. Like all developing nations, they struggle with poverty, under-funding for police and other institutions, and various social and infrastructural issues. Bolivia is large and much of its territory is remote: the high spine of the Andes to the west, dotted with tiny villages that might lack electricity but have a lovely art-filled conquest era church; the Amazon jungle to the east concealing poorly understood and difficult to monitor (or even locate) archaeological remains. In other words, Bolivia is motivated to protect their heritage, but practical realities often make such a task impossible.

These challenges have not stopped Bolivia from instituting a variety of sound policies for documenting and protecting their heritage. In particular, I remain impressed at their Ministry of Cultures’ initiative to document all known cultural heritage objects in the country. This is a legislative mandate that has been going on, at least in its current form, since the 1980s and represents one of the best and most complete set of national cultural property records in all of Latin America. Each object is fully described on a modern and standardized object reference form, measured, and photographed. Many of these objects are located in remote churches and the Ministry of Cultures’ forms represent the only inventory communities have of the cultural objects they interact with. When there has been a theft of known cultural property, Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures is uniquely able to respond by inventorying the loss and releasing photographs and descriptions of missing items to police, border agents, and abroad via the issuance of an INTERPOL alert. These ministry of culture files have been instrumental in a number of cultural property returns.

(3) application of import restrictions in the context of a concerted international effort, to archaeological or ethnological material of the State Party would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage, and less drastic remedies are not available;

As previously discussed, there is a clear and current market within the United States for Bolivian cultural objects: particularly colonial and ecclesiastical items and items corresponding to the Andean Middle Horizon. This market demand can be directly correlated with a spate of very recent and very devastating church thefts which, although centered in Bolivia, are also occurring in highland regions in neighboring Peru. These items are being trafficked into the United States. To remove import restrictions would open the floodgates, allowing stolen property to enter the US with impunity, and not only for Bolivian objects. Particularly with regard to Colonial and Republican pieces, which can be portrayed on the market as coming from a number of Andean locations, removing these restrictions at this time of high market demand may encourage laundering of cultural property through Bolivia which would weaken both the inter-South American state cultural property agreements that have been signed in recent years, and seriously undermine the existing cultural property MOU between the US and Peru.

(4) application of import restrictions in the particular circumstances is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific and educational purposes.

It is within the interests of the international community to protect and preserve Bolivian cultural property from theft and trafficking. While US/Bolivia relations have been complicated throughout the last decade, one area where we have consistently displayed fruitful partnership has been in the area of cultural heritage research and preservation. Bolivian heritage policy requires foreign archaeological projects to include a local co-director and local staff: a model that leads to life-long academic and research collaborations between Bolivian and US heritage professionals. It is through these ongoing professional partnerships that state-sanctioned agreements for loans of cultural objects for exhibition or study are formed. The illegal looting and trafficking of cultural objects from Bolivia destroys the very contexts that these cooperative teams study, eliminating all possibility for knowledge exchange.

It is within the interests of the international community to protect and preserve Bolivian cultural property from theft and trafficking. While US/Bolivia relations have been complicated throughout the last decade, one area where we have consistently displayed fruitful partnership has been in the area of cultural heritage research and preservation. Bolivian heritage policy requires foreign archaeological projects to include a local co-director and local staff: a model that leads to life-long academic and research collaborations between Bolivian and US heritage professionals. It is through these ongoing professional partnerships that state-sanctioned agreements for loans of cultural objects for exhibition or study are formed. The illegal looting and trafficking of cultural objects from Bolivia destroys the very contexts that these cooperative teams study, eliminating all possibility for knowledge exchange.

Let me be clear: there is absolutely no social, educational, or scientific benefit to allowing a market for illegally obtained Bolivian cultural objects to exist in the United States. The destruction of the original contexts of these objects in the looting process annihilates our ability to conduct any meaningful archaeological analysis on them. The violent removal of sacred art from churches tears the very fabric that has held small and indigenous communities together for centuries, reducing cultural diversity and survival and eliminating avenues for anthropological and sociological research. Bolivian cultural property is available to accredited international researchers for all manner of study within a structure that encourages knowledge sharing and international partnership. And on a general note, cultural tourism to Bolivia is on the rise, evidencing a global interest in the conservation of Bolivia’s cultural heritage.

I thank the members of the Committee for considering my thoughts on the matter. Bolivia is a beautiful and complex country that, despites centuries of social and political strife, has managed to retain its unique tangible and intangible cultural heritage. This heritage is woven in to all aspects of Bolivian public and private life; it is the very core of national, regional, community, and individual identity. It is difficult to overstate the prominence, the importance of the past in Bolivia. It is a shame that market demand within the United States has threatened and continues to threaten this past.

Yet again, I highly recommend the he extension of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Bolivia Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material from the Pre-Columbian Cultures and Certain Ethnological Material from the Colonial and Republican Periods of Bolivia. I remain at your disposal for any other information that I can offer in support of this.

Sincerely,

Donna Yates

Lecturer, School of Social and Political Sciences

University of Glasgow

Additional Resources

Yates, Donna (2015) Reality and Practicality: Challenges to Effective Cultural Property Policy on the Ground in Latin America. International Journal of Cultural Property 22 (2-3): 337–356.

Yates, Donna (2015) Looting, trafficking, and sale of illicit cultural property from Latin America. In Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods: The Global Challenge of Protecting the World’s Heritage, F. Desmarais (ed). Paris: ICOM.

Yates, Donna (2014) Church theft, insecurity, and community justice: the reality of source-end regulation of the market for illicit Bolivian cultural objects. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 20 (4): 445–457.

Yates, Donna (2012) Archaeological Practice and Political Change: Transitions and Transformations in the Use of the Past in Nationalist, Neoliberal and Indigenous Bolivia. PhD Dissertation. Department of Archeology, University of Cambridge.

Yates, Donna (2011) Archaeology and Autonomies: The Legal Framework of Heritage Management in a New Bolivia. The International Journal of Cultural Property 18(3): 291–307.