A taster abstract for one of the journal papers I have “in submission”.

Archaeological sites are looted, cultural objects are trafficked, and buyers purchase stolen artefacts. For decades we have known that the illicit trade in antiquities causes catastrophic damage to the archaeological record and threatens individual and community identity, cohesion, security, and sovereignty. An international regulatory regime, largely informed by the 1970 UNESCO convention, has been developed with a stated aim of protecting heritage sites, preventing looting and trafficking, and effecting returns of stolen cultural property. Unfortunately the regime falls short of these goals.

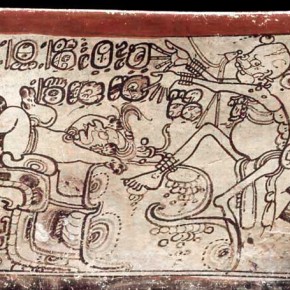

I will discuss a significant flaw in the focus of global cultural property policy using Maya antiquities and United States law as a case study. By prioritizing the country of origin of looted objects, policy that is ‘country-specific’, like most developed under the UNESCO convention, provides inadequate on-the-ground protection and does not disrupt antiquities smuggling networks. In contrast, ‘object-specific’ policy, which is focused on the presence of valid export permits no matter where an antiquity is said to come from, appears to be effective at preventing looting and trafficking. ‘Object-specific’ has worked for antiquities in the past, is working for similar illicit commodities in the present, and might be how we should protect our past in the future.