Second installment of my translations of a feature the La Razón published on cultural property crime in Bolivia

Trafficking Gangs Operate in Bolivia

This year there were two robberies of cultural property, with 115 pieces stolen. Interpol believes that the offenders have taken them to as many as five countries on other continents.

La Razón

5 November 2012

http://www.la-razon.com/suplementos/informe/Mafias-traficantes-operan-Bolivia_0_1716428485.html

The trafficking of cultural property is not only undertaken by huaqueros at Tiwanaku and its surrounding areas, or at the other archaeological ruins of the country, it also happens as a result of the complicity of custodians and people living near Colonial religious sanctuaries, according to information from the International Police (Interpol) in Bolivia, and at the same time government mechanisms for the protection of this heritage are still weak.

In August, the churches of Guaqi and Ocobaya in the provinces of Ingavi and South Yungas of [the Department of] La Paz, respectively, suffered the theft of relics that usually end up on the black market. “After the arms trade and the drugs trade, trafficking in cultural property is one of the easiest ways to obtain illicit money in the world, and the thefts at Colonial churches and of pre-Columbian objects are intense,” says the renowned Peruvian archaeologist Luis Lumbreras.

Control

Interpol explains that the primary threat to Bolivian relics is the illicit trade. “There is no good, effective control, the only thing that is applied is social control, as villagers (of the sites where there is looting) say, and even the help of the Ministry of Culture is not enough; because of this, when they [the villagers] find an ancient piece they sell it to foreigners”, related Colonel Álex Ríos.

Because this heritage is protected by the Political Constitution, article 331 of the Penal Code punishes their theft with one to five years in prison, and the penalty is increased to between three and ten years if the crime is committed with weapons or with the concealment of the identity of the agent by two or more individuals in a remote area; furthermore article 223 dictates that: “Whoever destroys, deteriorates, removes or exports an object that belongs in the public domain, a source of wealth, a monument or object of national archaeological, historical or artistic heritage, incurs a imprisonment from one to six years.

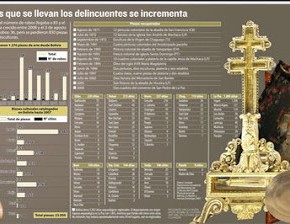

The statistics of the Unit of Intangible Heritage of the Ministry of Culture reveal that in the last 15 years there were at least 89 thefts that resulted in the disappearance of 1,276 heritage pieces. In 2011 there were four burglaries that [resulted in the theft of] 32 objects; and so far this year there were only two cases (those of Ocobaya and Guaqui), but the number of stolen relics amounts to 115.

Traffickers of archaeological pieces hire campeseños to dig into the subsoil of pre-Hispanic ruins, according to Interpol and archaeologists Jedú Sagárnaga and José Estévez; in the case of Colonial churches, the guardians or “stewards” are the primary suspects. Interpol warns that these people are contacted by gangs to remove objects, and then hand them over to “bridges” or “links” that lead to the end of the chain, the antiquities dealer or collector. The chain has national and international links.

Guaqui

Something like that happened in Guaqui between the night of Thursday 2 August and the morning of the next day, or at least that is what is suspected. There the image of Tata Santiago, as devotees know him, was the victim. Only the saint knows who stole 105 silver artefacts which were approximately 200 years old. “There has been an arrest; however it seems that it will be difficult to recover the items”, Eduardo Quispe, the neighbourhood leader, mutters with anger.

The event took place one week after the Patron Saint feast day, and according to guardian Ricardo Aguilar, the accusations point to a Peruvian citizen Teófilo Campos, who came last year to the village with the alleged intention of writing a biography of the late father Sebastián Fancella, and who asked to be housed in the basilica while he wrote his book. “He said that he was conducting interviews”, related the neighbourhood leader Rogelio Ticona. Now, Campos is apprehended in the San Pedro penitentiary in the city of La Paz.

The crime happened on exactly the night that Aguilar forgot to set the electronic alarm that protects the building. “I had not armed it, I forgot, I did not think this would happen, I have worked here for years”, argues the 64 year old man, trying to find an explanation for what happened. But Ticona has no doubt about what happened: “They had planned it (Aguilar and Campos), the caretaker knows where the cables go. They had been cut; the one who is directly responsible is him”.

The parish priest, Celso Garcilazo, admits that it was “unwise of the caretaker Aguilar”. However, what happened in Guaqui reflects the fundamental common denominators of the looting of cultural property. “Generally it is undertaken through the complicity of the caretaker or the person in charge of the custodianship of the churches and even those that have alarm systems, they are not activated and just on that day they forget to arm them and the objects are removed,” explains Colonel Ríos of Interpol.

Aguilar and one of his sons were the guards of the church during the past 15 years and each receives 300 Bolivianos to safeguard the ecclesiastical treasures––money that is paid from the savings of the church––because the communities of the municipality refused to send their people to undertake this task. When Aguilar returned to the site on the morning of Saturday the 4th of August, according to his story, the first thing he saw was the cut cables of the alarm. Now he is one of the suspects and has given his statement to the Prosecutor.

The first attempt to loot the riches of the church was in 2001, but on that occasion the alarm did its job and stopped the crime. The robbers fled, fearful of being caught by the villagers, and left a ladder and several blankets with which they intended to hide the silver ornaments. But it was a different story in August this year. “We were robbed of 80% of the silver and the altarpiece” says the priest Garcilazo, it is by the grace of God and Tata Santiago that 60 valuable Colonial paintings have not suffered the same bad luck. At the same time, those that managed this coup are the same people that robbed the church of Laja, in the Los Andes province.

Interpol reveals that the Internet is the preferred medium for traffickers to sell stolen relics. “There are international gangs operating particularly in Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, because of their cultural riches,” describes Colonel Ríos. The fate of these objects is the black markets that feed millionaires’ private collections, or antiquities collectors, or the collections of individuals in Canada, Spain, United States, Switzerland and even Japan.

Marcelo El Haibe, of Interpol Argentina, told AFP news agency in October that traffickers in historical artistic works operate in Peru, Bolivia, Guatemala, Ecuador, Argentina, Chile and Mexico because there is a high demand for archaeology, religious art, and paleontological remains whose destinations are the United States, Switzerland, Spain, Germany or Britain.

Because of this, Peru is about to create an elite police to fight this scourge.

Bolivia is also a transit nation for the removal of stolen heritage objects from other nations in the Andean region to other continents. This is because of a lack of border control. However, criminals are turning to other methods to undertake their crimes; for example, two years ago Bolivian police seized a Peruvian pre-Inca mummy that was 700 years old, which was meant to be sent to a European country through the postal service.

While the experts that were consulted believe that there must be greater border security, or that a Cultural Heritage Law must be designed to deal with trafficking in this area, or restate the idea of creating a Cultural Police Force, the minister of culture, Pablo Groux, believes that the first step is to register and catalogue cultural property at a national level. The Intangible Heritage Unit has a register that exceeds 20,000 pieces.

Concerns

During the festival of 25 July, security was doubled at the Colonial church in the village of Guaqui, but no local thought that evildoers would wait two weeks to strike the blow that has left the village worried and saddened. “Nobody was able to foresee that that was the night (between Thursday the 2nd and the morning of Friday the 3rd of August) that the thieves would come”, says pastor Garcilazo.

The Police, the Public Ministry, and the Ministry of Culture have investigated the theft; however, there are criticisms of their work during the investigations. “There was an oversight by the prosecutor and the investigation didn’t happen quickly. We waited from the 3rd of August and they arrived at 5 in the afternoon on the 7th of August”, complained the local leader Quispe, who also complained against the Municipality. “We have drawn attention to this because they should be the first to help and they only said that they were going to be interveners.”

Román Mamani, the other neighbourhood leader, commented that the mayor Víctor Mamani––who could not be reached by the La Rázon reporter––worked with the authorities to find the stolen relics. Meanwhile in the church, the curate Garcilazo seems resigned to the idea that he is not going to see the silver pieces of Tata Santiago again and, therefore, it is now the responsibility of devotees to help replace the relics whose whereabouts are unknown.

“There are no others, those of the recent or distant past, which are equal and we want to recreate them. God willing, perhaps you will find them; however I do not have much hope for that. The only thing left is for people to contribute.” The curate believes that the apostle Santiago “is hurt”, but that he forgives them for this desecration. “I wish that these people could repent”, he says.

The morning of Thursday 6th of October, when this horror visited Guaqui, the alarm was being repaired in this local church just like in Ocobaya––where a grown of gold, the caps of a cross, and three pieces of silver depicting Our Lord of the Exaltation in high relief were stolen––they are the only cases of theft of cultural property in this year.

Schools must take the first step

When will school books talk less about Greek and Roman art, and more “about our Indigenous communities starting to love, respect, and conserve our heritage”, opined the Argentine historian Fernando Soto.

The faculty member and researcher at the Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata believes that children should be of primary concern regarding historic heritage. “Without the direct intervention of the State and without an awareness program that is part of primary and secondary school, from early on, the battle against this scourge (trafficking in archaeological objects) will never be won”, explains Soto to the La Rázon reporter via email.

For the scholar, the heritage of colonialism works to our detriment. “There has been almost 500 years of self-underestimation and of a discourse that tells that that these objects would be better protected in museums in the First World”, says the specialist.

He placed the blame on the demand that exists in other countries for archaeological pieces, adding that only way to fight against this would be to fight the buyers of stolen cultural property in other nations. “The problem is with those who want [the objects], who are always private institutions that are very powerful economically”.

He admits, however, that in recent years, in some South American states, important steps have been taken to protect the archaeological and paleontological heritage. “Compared with the neoliberal policies of the 90s (when it was not only pre-Columbian pieces of our past that were sold, but whole chunks of our countries). So everything, everything that is done is still insufficient”, says the author of several books, articles and essays on archeology in South America.

At least 300 cultural treasures can be found outside of the country.

In 2006, Édgar Arandia, then Vice-minister of Culture, and now director of the National Museum of Art, undertook an inventory of Bolivian archaeological pieces that are located outside of the country. The preliminary report revealed that “there were at least 300 Pre-hispanic artefacts in other countries”, he says. He does not know of a similar study besides that one.

Currently there are doubts about the number of relics that are exhibited in other countries, of which it is important to know if they were displayed legally, in accordance with Bolivian law. For example, the Peruvian archaeologist Luis Lumbreras, one of the most renowned archaeologists in Latin America, relates that one of the main collections of Pre-columbian works from Bolivia is in the German capital: Berlin.

Tiwanaku

“One of the major collections of Bolivian pre-Hispanic art is that of the Museum of Ethnography of Berlin, where they have hundreds of great pieces”, said the specialist who is a professor of Social Studies at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos in Peru and who conducted a workshop in the city of La Paz in early October.

Arandia, who also serves as executive secretary of the Cultural Foundation of the Central Bank of Bolivia, confirms what Lumbreras said. “In Berlin there is a pre-Columbian stone that represents lightning, and in Denmark lithic tablets are exhibited.” Moreover, the Peruvian expert says, for example, many studies of Tiwanaku have been done based on works from this culture that are not in Bolivia. “A large part of the publications about Tiwanaku are based on pieces that are outside of the country”.

However, according to data from the Ministry of Culture, few pieces have been recovered from the hands of traffickers: there have been only 14 cases since 1971. Now, this division [the Ministry of Culture] is preparing an official request to Peru to recover archaeological pieces that belong to the Tiwanaku, Wari, and Inca cultures, which were seized three years ago in the neighbouring country, in an investigation that also involved historic pieces belonging to Ecuador and to Peru itself.

That nation is also dedicated to launching a frontal assault against the traffickers of these objects, according to the AFP. The Vice-minister of Heritage of the Ministry of Culture of Peru, Rafael Varón, commented that based on recent developments they are working on a plan to create a specialised police force focused on Cultural Heritage, like those that exist in the United States, Italy, and Argentina to train prosecutors and judges.

Objects for sale on the internet

I am selling a Keru (vase) from Late Tiwanaku IV. Piece complete with double frontal applied decoration (anthropomorphic and zoomorphic), painted decoration in monochrome bands, geometric motifs. State of preservation: average to good (rob******@hotmail.com)”. [I have removed the email address listed in the paper] The advertisement is on www.mundo.anuncio.com.bo [sic: http://www.mundoanuncio.bo/]; the piece is priced at $300 USD. Ex-prosecutor Milton Mendoza complained alleged pre-hispanic objects were being offered for sale on the internet.

Just like the sale of archaeological objects, a bolivian webpage is www.mercado.com.bo. On http://bo.clasificados.st/antiguedades an antique ceramic is for sale: “Urgent sale of an Inca carved stone that is approximately 1500 years old, according to the analysis performed by archaeologists who think that it is a phallic symbol that represents the virile power of man, I have a pressing need to sell it because of my health, and because of that I hope for an offer”.