A most unbelievable story of a looted (or fake) Maya book and mask.

Looted and trafficked cultural objects are often given a false background, find spot, and ownership history. We know this. Sellers make up plausible but totally fake stories that explain why the objects are in their possession, and which render the pieces sellable on the market.

No one actually believes these stories, but the better ones are just tight enough that they are hard to prove false. The lowest level is saying that a recently-looted piece comes from an ‘old family collection’ or an ‘Anonymous Swiss Collector’. Prove that it doesn’t? Go on! Even in the most unlikely of situations, these ‘false provenances’ can win out. Any museum, collector, dealer, or auction house that accepts a ‘maybe’, accepts vague provenance, should be given two swift kicks.

Every once in a while I come across an illicit antiquities origin story that is far and beyond most of the others; a story that is so unbelievable that it almost comes around to being believable again. Who would make something like this up? Who would believe it? Below is one of my ‘favorites’.

A VERY unlikely story: Mexican banditos as antiquities dealers

This story is mostly taken from Coe (1992) and Meyer (1973), supposedly from accounts told by collector Josué Sáenz and dealer Alphonse Jax.

As the story goes 1966 a Mexican City-based antiquities collector named Dr. Josué Sáenz was phoned by a man who called himself ‘Gonzáles’. Gonzáles called three times, promising non-specificed ancient treasures, but demanded that Sáenz take the first flight to Villahermosa, Tabasco. Sáenz agreed to this deal and got himself to Villahermosa. There Sáenz was met by a group of, apparently, terrifying strangers who convinced him to get into a small plane. They covered the compass with a cloth and took off. Eventually, they landed in a remote airstrip somewhere in the foothills of the Sierra de Chiapas (Sáenz claimed to be familiar with the region so knew roughly where he was). The plane was approached by a group of rough-looking villagers.

The collector just hopped on a small plane and flew into the Sierra de Chiapas with terrifying strangers.

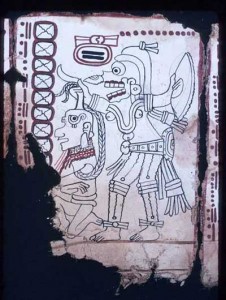

Quite quickly, the villagers unveiled their treasures: a spectacular mosaic Maya mask and what may be one of only four surviving Maya books or codices. Oh yeah, some other stuff too. Anyhow the villagers told Sáenz that they had found the items in a dry cave and that they were for sale. Sáenz asked to take the antiquities back to Mexico City to have them authenticated but the villagers refused, saying he had to make a decision about the items right then and there. Sáenz offered the villagers $2,000 for the mask and codex, but they, in turn, produced an auction catalogue from the house Parke-Bernet and indicated they knew the US sale value of Mexican antiquities and did not want to be cheated. Sáenz then wrote a post-dated cheque for a higher amount and took possession of the mask and codex.

The Story of the Mask

Back in Mexico city Sáenz showed the mask to José Luis Franco, an art expert and authenticator, who felt that it was probably a fake. Sáenz then put a stop purchase order on his cheque for the piece but found it had already been cashed. Sáenz, annoyed at the situation, turned the mask over to a dealer he worked with, instructing the dealer to sell it with no guarantee of authenticity. This dealer sold it on to New York-based dealer Alphonse Jax and the piece was moved into the United States under dubious import circumstances.

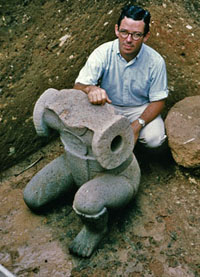

Questions about the authenticity of the mask remained which was a problem for Jax. The dealer allegedly showed the piece to Dr. Gordon Ekholm, the curator of Mexican archaeology at the American Museum of Natural History who examined the mask under a microscope and found what he believed to be evidence that a beard had once been attached. Ekhole believed that such a fine detail that he felt forgers would not include. As you can imagine Ekholm’s declaration that the mask was genuine “considerably enhanced the value of the mask”. The mask is now widely considered to be genuine and it was sold to Mildred Barns Bliss in 1966…the same year it was allegedly found.

The Story of the Codex

In 1970 or 1971 Sáenz showed archaeologist Michael Coe the codex, seemingly the first time he showed it to anyone. To restate that in another way, Sáenz allegedly had in his possession one of the most rare and significant archaeological finds for at least four years and didn’t bother to tell anyone. It had long been thought that the fragile nature of fig bark paper and the wet, acidic soils of Mesoamerica would effectively prevent codices from being found within archaeological contexts. All previous codecies to appear on the market were found to be fakes. Coe felt this one was different.

Coe convinced Sáenz to display the codex at the Grolier Club, New York, in an exhibition entitled ‘Ancient Maya Calligraphy’, organised in 1971 where it got the name “Grolier Codex”. Coe was initially coy about revealing the owner of the piece. In his 1973 catalogue of the exhibition that included the Grolier Codex, its owner is listed, inaccurately, as ‘Collection: private collection, New York’. When contacted by Karl E. Meyer in 1973, Coe would only say that ‘the codex was a “real hot potato” lent to the Grolier Club by an anonymous owner’ and would say no more on the matter. The Grolier Codex was eventually donated to the Mexican Government, although the timing and the circumstances of that donation are unclear.

Many researchers believe that the Grolier Codex is a fake. Beyond the, well, interesting story of its discovery and the fact that Sáenz sat on it for a number of years, some researchers find issues with its contents. A convincing radiocarbon date was produced for the piece, but it is not unheard of for blank fig bark paper to be found in archaeological contexts: a forger would simply have to paint on it. Recent scientific analysis of the Grolier Codex detected ‘induced degradation’: cuts along the edges seemed sharp as if made by a blade and supposed water staining around the edges of the codex do not permeate the surface of the paper Water staining looked as if ‘two or three subsequent drops of dye or ink were carefully applied to the top’.

That said, because the codex appeared as a looted, unexcavated, and potentially-trafficked antiquity, we will always have questions about it.

Is the discovery story a lie?

Probably yes. Here is why.

Let’s face it: archaeology isn’t like the movies and neither is antiquities looting and trafficking. The idea of a wealthy Mexican doctor just hopping on to a plane with a bunch of anonymous banditos in the mid 60s is beyond absurd. Buying the stuff on the spot like that for a large sum is crazy talk. Saying that the villagers had an auction catalogue on them is the stuff of fancy-dinner-party-filled-with-horrible-rich-people chatter. But the story serves a purpose.

Let’s face it: archaeology isn’t like the movies and neither is antiquities looting and trafficking. The idea of a wealthy Mexican doctor just hopping on to a plane with a bunch of anonymous banditos in the mid 60s is beyond absurd. Buying the stuff on the spot like that for a large sum is crazy talk. Saying that the villagers had an auction catalogue on them is the stuff of fancy-dinner-party-filled-with-horrible-rich-people chatter. But the story serves a purpose.

Sáenz ended up with what he likely felt were two entirely unrelated fakes that he bought off the regular Mexican antiquities market. The mask has since been accepted as ‘real’ (probably to Sáenz’ dismay as he likely didn’t get much for it) and the codex as highly questionable, but at one point Sáenz had to save face for some poor purchases and to try to give the fake(s) a background. So he made up a ridiculous story…which he seemed to have used at least twice, once on the mask in the 60s and once on the codex in the 70s. No longer were these poor purchases, they were stepping stones towards the image of the swashbuckling antiquities collector. They brought a certain feeling of authenticity to these looted/fake pieces. They make the pieces sellable. Even with the story Sáenz unloaded the mask and didn’t tell anyone about the codex until Coe came nosing around…and then didn’t want his name on the codex when it was displayed.

We are one step away from buying them from an Anonymous Swiss Collector…just this time it is Anonymous Mexican Banditos.