“Sweden Returns Ancient Andean Textiles to Peru“. Now that is a headline I like to see.

The piece, by Ralph Blumenthal, goes on to detail the start of a return of a large collection of Paracas textiles held by the National Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg. This return has been a long time coming.

The story of how these textiles ended up in Sweden perfectly illustrates various aspects of the illicit trafficking of antiquities: a site that was discovered first by looters; protection during archaeological excavation; massive looting when political issues caused archaeologists to leave the site; instant illegal export; developing/developed world divide. The following is derived from my article on Paracas Textiles from the Trafficking Culture Encyclopedia.

The discovery of Paracas

“Paracas” is a rather loose term that is applied, broadly, to things that were happening on Peru’s Paracas peninsula from around 800 to 100 BC. It can refer to two related but distinct cultural complexes (‘Paracas Cavernas’ and ‘Paracas Necropolis’), a textile style (divided into the same two groups), a ceramic style (the Necropolis version is sometimes called Topará), and the region where all of this stuff is found.

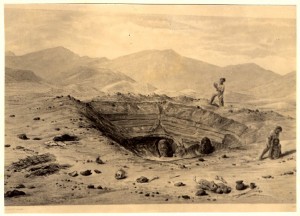

The great Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello first described the Paracas culture in the 1920s after various Paracas sites had been sacked by looters. Tello noticed with dismay that a number of high quality looted textiles were appearing on the Lima antiquities market and decided to find their source. In 1925 he received a tip that beautiful textiles were being looted from the site of Cabeza Larga on the Paracas peninsula. With the help of local huaqueros, Tello was able to match textile fragments found at Cabeza Larga to the style of the looted pieces he had seen for sale.

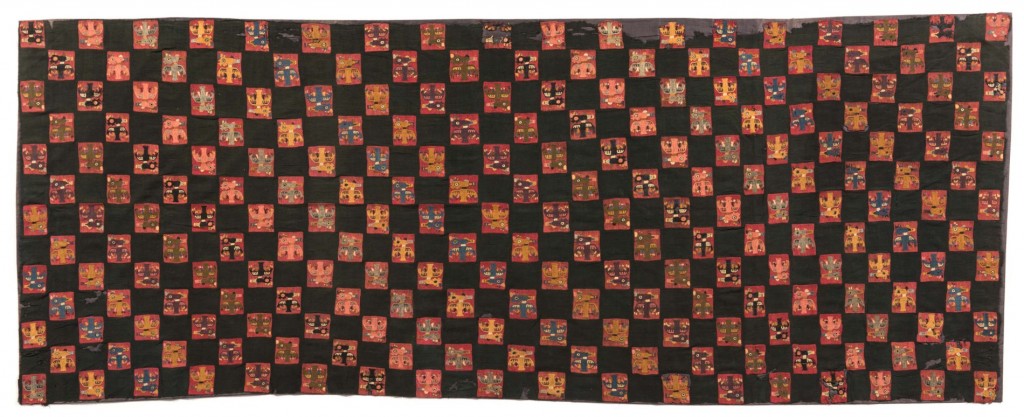

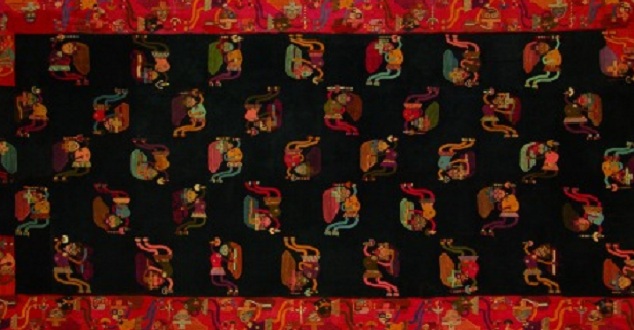

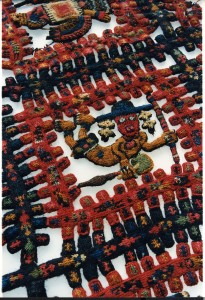

Over the course of several years and through intense archaeological investigation, Tello and his team excavated at Paracas. What they found was astonishing. Because of the hot, dry nature of the peninsula everything they found was in a remarkable state of preservation. Of particular note were the so-called ‘mummy bundles’: Paracas bodies, tied in a seated position in a basket, and wrapped in layer upon layer of beautifully woven and embroidered fabric. Paracas textiles are considered to be among the highest achievements of textile art, among the finest in the world. Tello recovered 394 of them.

The looting of Paracas

In 1930 Tello was forced to resign his position as director of the Museum of Peruvian Archaeology for political reasons. Paracas was left unprotected and was almost immediately hit by looters. Tello reported that looters were digging in areas that were still marked by archaeological surveying stakes. From 1931 until 1933 looting at the site went unchecked. Tello and others reported human body parts scattered on the surface at Paracas. Textiles from the site hit the market immediately and were exported illegally abroad. This is where the textiles in Sweden come from.

Between 1931 and 1933, exactly the years that Paracas was sacked by looters, the Swedish Consul General in Peru began exporting ancient textiles to Gothenburg. The Consul, Sven Karell, appears to have sent 100 textiles back to Sweden to form a collection in what would become the Museum of World Culture (new shelving to house the textiles was ordered in 1932). They moved to various locations in Gothenburg and were stored in various questionable ways. Some are now in very bad shape. Moving many of them is now very difficult which is rough because Peru, rightly, wants them back.

Return of the Gothenburg Collection

According to the Museum of World Culture, the textiles were indeed “illegally exported”. Why do we know this? Because the Paracas site wasn’t truly looted until Tello left the site in 1931 and that is roughly the same year that the Consul General sent the items to Sweden. Thus we can say that the pieces were looted and trafficked in 1931/32 and that their removal was, of course, in violation of Peru’s 1929 antiquities legislation. It is refreshing that no one is contesting that.

In 2009 the government of Peru requested the return of the collection and in 2010 Gothenburg agreed to the (slow, careful) return of the pieces. In a weird move, then-president of Peru Alan Garcia announced in 2011 that legal action would be taken against the city of Gothenburg for the return of the textiles, claiming that the city government was ‘complicit in the deprecation and looting of a country and civilization’. This, no doubt, came as a surprise to Peru’s own government heritage folks who were working to develop a safe plan for the textiles’ return at the time. Those comments were ignored/forgotten because they were mad.

So there we have it. On 18 June the first four, the most robust of the lot, will go back. Others will slowly follow as they are stabilized and the last is expected to be returned in 2021.

Cost of continued care

The cost of conservation is an aspect of repatriation that we rarely speak about. Yes it is great that Gothenburg has fully admitted that they have been holding stolen property, smuggled in the name of the Swedish government, for decades. But that doesn’t really help Peru, a country whose skilled conservators now have to deal with a string of poor conservation and display decisions made by Swedish museums. It is impossible to speculate if the textiles would have been better conserved in Peru (although, of course, we could look to the Tello collection…), but the fact is that after 2021, all of the issues associated with care, cleaning, and preservation are now Peru’s problem.

I am unaware of any repatriation agreement which includes the (inevitably Western, developed world) institution paying for the continued care of the objects returned, even in situations where the decidedly more cash-strapped nation that the object originally came from inherit a mess. I think in this case Gothenburg is fronting much of the funds to stabilize the textiles and are clearly paying to house them until they can be moved; I am not criticising this partnership at all. However, very little work has been done on ‘after the return’ regarding costs to the receiving institution vs, perhaps, increase in revenue from admission paying visitors and tourism increases. There is a PhD topic in that for someone.

All in all, I am glad these textiles are finally trickling back. I am glad that they will be near the original Tello collection for comparison and study. I am glad that the institution holding the textiles fully acknowledged their illegal export and has done the right thing. And I am glad that this return is getting some press. More museums should take note!