Thoughts on professional inaction

A story I posted on twitter and some comments I made spun into a forked debate: 1) how can archaeologists modify and change the way our profession is presented in the popular press and 2) what can archaeologists do to aid research into the illicit antiquities trade.

I, of course, was interested in the second. Although twitter is certainly not the place to grumble about such things, I made a series of tweets decrying archaeological complacency when it comes to a massive swath of transnational crime that just happens to threaten our livelihoods. I asserted every archaeologist could and should do more, but won’t.

I was asked to come up with a list of things that archaeologists can do to really help prevent the looting of archaeological sites and the trafficking of antiquities. I agreed. This will not be an exhaustive list by far, just some of my own thoughts. Higher-ups, if you are reading this, don’t slam me for it! Heck, no one slam me for it, please!

I must admit I still believe that archaeologists won’t do most or any of these things: extra work plus our human tendency to do the least but cast it in the mind as ‘every little bit counts’. It doesn’t. I’ve been at this for a decade now and nearly nothing has been as surprising as the lack of true engagement by most archaeologists. I love you guys, but it is true. And with that, I lose all my friends. Here goes:

1. Contribute to the Trafficking Culture website

This is the easiest on the list: it requires nearly no time what-so-ever. Yet over the last year I have made many calls for contributions with almost no uptake. On our site we have a Data section where we publish ANYTHING that people send in: photos, videos, audio, raw data, unpublished articles, half-finished reports, things we don’t even know about yet. We believe that there is a lot of information out there on modern and historic looting and that making it free and available brings us forward. Case-in-point, the Google Earth images of the looting of Apamea, Syria, kindly given to us by Dr Ignacio Arce, have received a massive amount of international press attention. You’ve probably seen them already or heard of them. Images of the looting of the Maya site of Placeres, kindly given by Prof David Freidel and actually okay-ed by the guy sawing-up the temple in the photos, have now been featured by Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, they didn’t have them before (although they had the temple facade back). I know that archaeologists take photos of looting and various other related things. I know they have info…but why don’t they send it in? Why don’t you-all send it in?

Mayanists, I am looking at you. I know y’all have surveyed the looters trenches on your sites, yet I have no data here from you.

The other way you can contribute to the website is to write an entry or two for our case-study encyclopedia. We started this section of the website to try and offer an alternative to the disinformation that is out there. The entires are short, but academic and fully researched/referenced. They are sound-bites, but reliable sound-bites. To contribute you need a little bit of specialised knowledge about either a looting/theft case or a law. That said, they are shorter than this blog entry. Know the story of the looting of a site or object in your geographic area? Why don’t you write it up for us. These case-studies, too, are quoted in the popular press (which raises the tone of those articles) and are used by researchers and students. Heck, why not assign case-study writing to your heritage masters students? The best results can be submitted to us for review and possible publication. A note: we are strict about these and they undergo internal and external review mostly for legal issues.

Email me if you are ready to contribute.

2. Make documenting of looting a permanent part of your archaeological project

Really. No one does this. If you do do it, you don’t tell us and you don’t send in or publish the results so it is pretty much the same as not having done it.

Really. No one does this. If you do do it, you don’t tell us and you don’t send in or publish the results so it is pretty much the same as not having done it.

There are a number of ways you can incorporate looting recording into your projects and, in many cases, you can make a field-school student or two do the grunt work. Brodie and Contreras have developed a methodology using Google Earth and then surface survey to quantify past looting and produce locally and internationally comparative data. They have tried it out in Jordan and Peru and have published it in a number of journals as well as online on a variety of websites, including our own. It is easy enough, super cheap/free and those kinds of numbers would be AMAZING. An archaeological project could do just their site or, heck, their whole region in not very much time. I think Brodie and Contreras thought archaeologists actually would start doing this.

They didn’t. Almost not at all. Come ON you guys!

Another thing you can do is local ethnography. Low-level, but start recording how communities talk about site looting, about cultural property, etc. Ask them about thefts, you’d be surprised how much people know and how much they are willing to share. Send me the transcripts…heck send me the recordings. Send me notes on what you heard. Again no one does this and, if they do, they don’t share it with us or with anyone so they might as well not have done this.

Anyhow, those are just two ideas, I can give you more.

3. Know the law…and follow it to the letter.

You think you know archaeological and heritage law/regulation where you dig? I bet you don’t. Almost no one does. Yeah I know, you believe you are different… What is the maximum sentence for illegal digging in your region? For trafficking? Legally must artefact dealers be registered? What is the cut-of-date for state ownership of cultural property in the country you work in? How many bilateral cultural property agreements has your country signed? Etc.

You think you know archaeological and heritage law/regulation where you dig? I bet you don’t. Almost no one does. Yeah I know, you believe you are different… What is the maximum sentence for illegal digging in your region? For trafficking? Legally must artefact dealers be registered? What is the cut-of-date for state ownership of cultural property in the country you work in? How many bilateral cultural property agreements has your country signed? Etc.

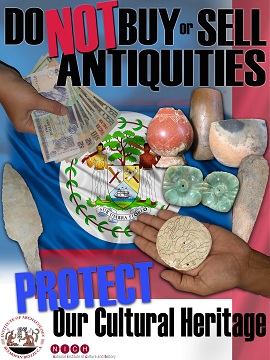

Sure you might know the gist of things, but we archaeologists are terrible for actually knowing the particulars of the very regulations that govern our work and protect the sites and objects we care about. This is double true for archaeologists who work abroad and in the developing world. I dug in Belize, Guatemala, and Bolivia before I knew two cents about the laws in those countries. Now I know the law in these places inside and out (intimately when it comes to Bolivia’s laws ) and, I’m going to tell you, we broke the law (in minor ways). You likely have too.

Where this becomes really important is in discussing what is legal and what is illegal with the community/press/public/government. Last week I had a bit of a snip at an alleged University of Arizona archaeology PhD student who, in a popular press article, was offering ethically questionable advice and, more importantly, was misrepresenting the law to readers and artefact dealers/collectors. We archaeologists are in a position of academic authority, we really are, yet we often know the least about the laws that protect archaeology. We are disengaged with the entire legal process, which brings me to:

4. Follow policy development and influence it

At the lowest-level, write letters at key moments when legislation or agreements are being considered or reviewed. You are an expert, offer your expertise and make it meaningful. This means you have to follow regulatory development in the country you live in, the country you work in, and any country that might be negotiating with either the country you live in or the country you work in. It is hard work following this, but these are the regulations that YOU will have to live with. Ten years down the line when your site is looted because of poor or de-regulation, or when you have to undergo insane formalities it will be your fault that you didn’t do anything.

At the lowest-level, write letters at key moments when legislation or agreements are being considered or reviewed. You are an expert, offer your expertise and make it meaningful. This means you have to follow regulatory development in the country you live in, the country you work in, and any country that might be negotiating with either the country you live in or the country you work in. It is hard work following this, but these are the regulations that YOU will have to live with. Ten years down the line when your site is looted because of poor or de-regulation, or when you have to undergo insane formalities it will be your fault that you didn’t do anything.

Yet, for the most part, archaeologists do very little. In the US every 5 years the various cultural property agreements we have with other countries are reviewed by the State Department. There is an open call for comment on the agreements and interested parties are asked to submit letters or even testify in DC. In my experience, in the countries I work in, you can’t convince most archaeologists to write even the least useful support letter for the agreement, let alone truly useful letters that take into account what the State Department committee is looking for. Yet we HAVE the information they are looking for. Why aren’t there 300 letters from archaeologists for every one of these cultural property agreements? I spoke at the last renewal of the US/Bolivia agreement and it was mental. Where WERE you guys? The excuse that no one told you it was going on is poor: you should actively be following this stuff. This is your livelihood.

Finally, the big one, crusade for better policy. Actually help craft local guidelines, national legislation (in your own country and in the country you work in), and international regulation. You can do this. It means talking to politicians (local and national) and pushing your agenda. Great thing about this is that it can almost always take place in the pub. Foster and expand your relationships with government officials. They matter.

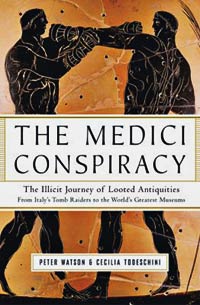

5. Help the press, talk to them…and never forget to mention threats to archaeology

There was a lot of press-trashing on twitter last night but, let me ask you archaeologists, how many of you know a good high-profile reporter that you can call with hot tips that the public needs to know about? I know several in a number of countries, and within our workgroup we know quite a few more. Investigative reporting has been some of the most useful and effective work against the trafficking of cultural objects. It very publically shames the market and that is what we need. Desperately. We need market shame. Do you all read Jason Felch’s (LA Times) Chasing Aphrodite Blog? You should.

There was a lot of press-trashing on twitter last night but, let me ask you archaeologists, how many of you know a good high-profile reporter that you can call with hot tips that the public needs to know about? I know several in a number of countries, and within our workgroup we know quite a few more. Investigative reporting has been some of the most useful and effective work against the trafficking of cultural objects. It very publically shames the market and that is what we need. Desperately. We need market shame. Do you all read Jason Felch’s (LA Times) Chasing Aphrodite Blog? You should.

With all the grumbles about archaeology being poorly represented and all the desire to make reporting better, I wonder why y’all don’t make it better by cultivating relationships with the press, feeding info to reporters who get it right, providing accurate info to or even co-authoring news stories, being proactive, and opening yourself up to high-quality interviews.

For example: last August I got a little sniffly about how the the robbery of silver from the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Copacabana was being portrayed in the media. I voiced my concerns and I was quickly contacted by the Associated Press for South America. The result was a long feature on my own pet issue: looting of conquest-era churches in the Andes. I thought the article was quite good, but I didn’t just give it a light touch. It was the result of two long emails to a Bolivian reporter (which were in Spanish…anyone who knows me knows how hard that was for me), and then a 45 minute phone interview on a terrible Bolivian landline, despite my need to be somewhere else for fieldwork. Why? Because it was important to me that things were right in the article. And you know what? It was reported widely and a lot of people read it. Are you all willing to identify the problem, take a massive amount of time communicating it effectively to reporters, and then opening yourself up to further work with them?

A final note. Destruction of archaeological sites and objects is a big thing. When you talk to the press about anything archaeological, always include some words on preservation issues. Always. Stress it. I’ve started to see this in the press lately: ‘We made this big discovery, look at it! So pretty! But we were scared it might get robbed before we got there, wouldn’t it have been sad if looters got it first and we couldn’t all enjoy it?’ That is a GREAT narrative. Work it in. Change the tone.

6. Demand that your university have an undergraduate and a graduate archaeological ethics and law course.

You shouldn’t get a degree in archaeology without passing one of these. If there is no course like this at your Uni (and I mean FULL course, not one or two lectures), or if that course isn’t required, fix the problem. Teach it yourself, share or borrow a syllabus.

You shouldn’t get a degree in archaeology without passing one of these. If there is no course like this at your Uni (and I mean FULL course, not one or two lectures), or if that course isn’t required, fix the problem. Teach it yourself, share or borrow a syllabus.

Or, of course, get me in to teach it as a guest for a semester! Email me.

In 2004, my last semester of undergraduate, I took an archaeological ethics and law course taught by the former head of antiquities of a country with a HUGE antiquities smuggling problem. It was great. Look at me now. I have no clue why we are sending students off into the world without this. If you are offering an archaeology degree without this sort of course, you are offering an inferior archaeology degree. Students? Demand this from your institution.

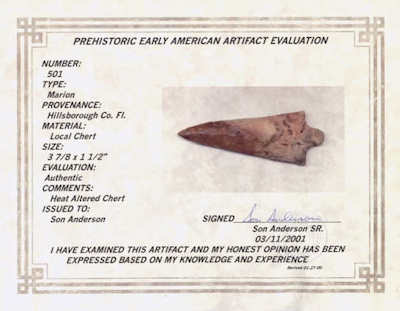

7. DO. NOT. AUTHENTICATE.

Never ever ever ever ever authenticate an object that anyone brings to you unless they show you an extensive paper trail. Even then, don’t authenticate it unless it was excavated archaeologically. Don’t sniff positively at it. Don’t. Not even if it has been out of it’s country of origin for 50 years. Don’t. You are legitimising the trade when you do.

Never ever ever ever ever authenticate an object that anyone brings to you unless they show you an extensive paper trail. Even then, don’t authenticate it unless it was excavated archaeologically. Don’t sniff positively at it. Don’t. Not even if it has been out of it’s country of origin for 50 years. Don’t. You are legitimising the trade when you do.

Yet, people do this all the time in big and small ways. You may not even think you are doing it. I fear I have probably done it in the past. We like to know things. We think a small nod, with a warning about illegality doesn’t constitute a problem. It does. Furthermore, in many fields there is a lot of pressure to find new material to publish, particularly, it seems, in fields related to epigraphy and linguistics. Even if you pass up the object, a less ethical scholar will not pass it up and that person will gain all the academic benefits of publishing the material. You have to be okay with this. You have to be better than that person.

You also have to be okay with calling out the people who DO publish the pieces. In academic meetings, in journals, in the press. It is hard to do this well without sounding like a jerk. Trust me.

8. Step out of your area of focus and read what we publish

Actually, this might be the easiest of the lot. Know what is going on in this area of research. Read the new papers, not the old ones. We put them all up for free on our website and there is even an RSS feed. Yes, you have limited time for papers and you should focus on your own field, but you might not have a field one day if your site gets looted. In these papers are ideas of things that you and your students and colleagues can do. Inspiration. Far better than any list I could churn out.

That’s it for now folks. Again, not an exhaustive list, but these are the sort of real and useful things you can, should, don’t, and won’t do. I promise I am not completely jaded, but I am pretty jaded. Go ahead, prove me wrong! I’d like that.