In this post I want to talk a little bit about the (very) little that I know about the Barbier-Mueller collection. As you can imagine, this mostly concerns shady dealings with particular objects, none of which are in the 22/23 March Sotheby’s Paris sale, none of which will probably ‘surface’ anytime soon. Indeed, my most favorite looted antiquity may (or may not!) be in the Barbier-Mueller collection: the Rio Azul mask.

The shape and contents of the Barbier-Mueller Collection as it stands today seems to have much more to do with the activities of the Barbier-Muellers in the latter part of the 20th century rather than the collecting of Mueller in the early part of the 20th century. Call me out on this if I am wrong, but see below.

Why are they selling this stuff?

Well, in 1997 the

Museu Barbier-Mueller d’Art Precolombí opened in Barcelona specifically to house the Latin American stuff from the

Barbier-Mueller central in Geneva. On 14 September 2012, Barbier-Mueller Barcelona

closed because it was not economically viable. The museum was unable to reach an agreement with Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller, who seems to have decided to scrap the whole thing. The objects in Barbier-Mueller Barcelona were sent back to Switzerland and Jean Paul set about selling some portion of them. Enter the Sotheby’s sale…which was announced the same month that Barbier-Mueller Barcelona shut its doors.

What is being sold?

The portion of the Barbier-Mueller collection being sold at Sotheby’s is pretty much your standard hodge-podge of “Precolumbian” things from up and down the Americas. Indeed, contents of the sale catalogue is not unlike the catalogues produced for several decades of Sotheby’s New York’s

biannual Precolombian sale. Plenty of these items came through those sales. At least one (lot 13) came from my pet ‘favorite’ dealer at the moment, the late

Everett Rassiga.

Everything is pretty standard marketable stuff: the popular things people buy for whatever reason. To go a step further, a lot of the items are exactly the sorts that have been (controversially) called fakes by Karen O. Bruhns and Nancy L. Kelker in

Faking Ancient Mesoamerica and in

Faking the Ancient Andes. I can certainly see how many of these things are just too perfect, too appealing, too modern, and totally unknown in the actual archaeological record. Take that with a grain of salt, but don’t just accept these things are all ‘real’.

How is the provenance?

This section is partially in response to criticism over Peru’s action to recover the Peruvian items in the auction. Reporting on the issue makes it seem that the collection is all pre-1920s and that Peru is acting anyway.

Other commentators have stated that this is evidence “that museums and others were snookered into accepting a 1970 date for acquisitions of artifacts”, stating that such a claim is unreasonable.

I don’t want to go into the 1970-or-not debate, but I think it is worth having a look at the provenance of these objects before we start saying such things. Why? As I said, Sotheby’s REALLY wants you to think that all of this stuff appeared in Switzerland magically in the 1920s. That simply isn’t reality.

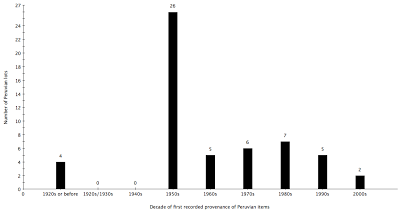

Like a madwoman, I have gone through the whole catalogue and recorded the listed ‘surface date’ of each of the items for sale. I am being very liberal and trusting the listed date-of-purchase from other galleries/dealers (usually I only trust publications and exhibitions because, well, people lie). The only thing I won’t accept is a date with no name (no Anonymous Swiss Collectors)… those I kick up to the next date (there aren’t many of these). Remember the house and the owners are motivated to push the provenance date as far back as they possibly can so we have every reason to believe that the dates listed are the earliest records for these objects.

Here is what we have in this sale:

So, 152 lots with provenance dates before 1970 and 161 lots with provenance dates after 1970.

Isolating the Peruvian items we get a different picture:

For Peruvian lots, 35 have provenance dates before 1970 and 20 have provenance dates to after 1970. Please note that in all of these, especially the Peruvian items, many are listed as simply ‘avant 1952’ when I suppose an inventory of the collection was taken. Make of that what you will.

What does this mean for Peru’s case?

Almost nothing. Although 1970 is bandied about, complained about, and called upon, and dismissed, the Government of Peru did not give up legal ownership of archaeological material upon signing the UNESCO convention. Peru is asserting ownership and, thus, illegal export. Ownership. Just like a private citizen could (you know, if you could privately own such things in Peru). I understand that assertions of ownership across borders is a bit of a dog’s breakfast: it is difficult to sort out, difficult to understand, and difficult to talk about, but under Peruvian law, Peru has owned all archaeological things since 1929 (

or perhaps 1822). How foreign courts interpret this based on their own law is, well, up to those foreign courts but there really is no practical reason to make the 1970 date more than it is.

And, again, the slight majority of items in this sale are post-1970 anyway so are unclean no matter how you look at it.

Now where is Guatemala in all this?

During the 1990s the mask was rumoured to be in a private collection in Germany, having passed through Switzerland (Adams 1999: 216). In late 1999 the piece surfaced in a temporary exhibition in the Barbier-Mueller Pre-Columbian Art Museum in Barcelona where it was seen by several Guatemalan government officials (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 4). In July 2001, the government of Guatemala issued a legal claim for the Río Azul mask as well as 11 other Guatemalan items in the Barbier-Mueller collection (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 60; Valdés 2006: 94). This process, documented extensively in Hernández Sánchez (2008), came to an end in 2002 when a Barcelona court denied Guatemala’s claim, stating that any alleged crime would have occurred outside of Spain’s jurisdiction (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 61). The mask is thought to still be in the Barbier-Mueller collection, having been moved back to Switzerland, but its exact whereabouts remain unknown (Hernández Sánchez 2008; Nessi 2008).

A TON of the items for sale at Sotheby’s are from Guatemala. Many of the ‘freshest’ artefacts, the ones with provenance dates in the 2000s, are Maya. I am not sure what kind of crossover there is with the 12 items that Guatemala unsuccessfully laid claim to a few years ago, but I would have thought they might have a go at these, especially if Peru is getting involved. Perhaps they are sitting back and letting Peru spend the money (if, indeed, any money is being spent, who knows). Let us see what happens.

PS: Rio Azul Mask!