My own (horribly flawed, terrible, I am sure) translation of a story by Jorge Quispe in the Bolivian paper La Razón this morning.

La Razon did a big cover story, three articles, on this issue today. Good for them. I’ll translate them for you all in the next few days.

For better or for worse, it is worth having discussions about this kind of stuff in Bolivia and if it is in English, it will travel. If you all are into it, I may translate more articulos from español to English as they come up.

—

Relics for Sale at Tiwanaku

A museum official offers pre-Hispanic vases. In the village and surrounding areas there prevails a black market in these pieces.

La Razón/ Jorge Quispe

5 October 2012

http://www.la-razon.com/suplementos/informe/Reliquias-venta-Tiwanaku_0_1718228195.html

“Right now this could be 150… 150 dollars”. This is how Zacarías Limachi offers for sale a supposed pre-Columbian vase of approximately 30 cm in size. He sits on the patio of his house, two blocks from the ancient ruins of Tiwanaku, in the Ingavi Province of [the District of] La Paz.

The inhabitant of the nearby community of Huacullani is a connoisseur of pre-Hispanic ceramics, because he is also one of the guards of the Museum of Tiwanaku, the most important archaeological center in Bolivia. “And the little ones, how much are they?”, asks the buyer and the man, who wears the uniform of the [Tiwanaku archaeological] repository, responded in a cautious tone. “This one is 100 and the other is 50 (dollars)”.

The first object has zoomorphic figures on it and the other two are a vase of 25 cm, without decoration, and a sort of small plate. In mid September, Limachi had offered the three relics for 350 Bolivianos each. However, now their prices have gone up. “You know how it is, boss! It is not possible to buy [these items]. It is also not possible to sell them right now, that is prohibited as well…”, so defends the campesiño upon noting the stranger’s interest.

Authentic

The buying and selling of the pieces encountered is prohibited by law. Article 99 of the Political Constitution dictates that Cultural Patrimony of the Bolivian people––natural, archaeological, paleontological, historical, documentary resources and those items that pertain to religious orders and to folklore––is inalienable, non seizable, and imprescriptible, and the State guarantees their registration, protection, restoration, recuperation, revitalization, enrichment, promotion, and distribution.

According to Limachi, the trio of fragments that he offers were extracted from his property in Huacullani, two and a half hours from Tiwanaku, a village where there was formerly archaeological excavations. However, the municipal official is considered a man with little luck because other people from Huacullani have found better pieces. “They searched in my place and one (of the others) had already looted another vessel, better than these”.

He is not the only huaquero or excavator, people who dig in the ground to find object made by the ancestors, to sell to tourists or collectors, in this area. They are at the end of the black market chain for this category. Locals even stock ‘private museums’ in their houses with objects they recover; the cost to observe and see them is around 10 Bolivianos. And, just the same, there are scammers who offer fakes for sale.

The archaeologists Jedú Sagárnaga and José Estévez agree that this region is the source of the relics, that the excavations undertaken by experts only account for 5% to 8% of the territory that the Tiwanaku culture inhabited, over 3,500 years ago [sic] and until their enigmatic disappearance in the 12th century of the present era, the vestiges of which are 70 km from the city of La Paz, 10 km from the shores of Lake Titicaca, at approximately 3,485 m above sea level.

The buyer that contacted Limachi gave a the La Razón reporter photos and a video (available at www.la-razon.com) in which one can see and hear the official employee bargaining for the three relics that, according to the archaeologist Sagárnaga, are originals to a degree of certainty of 90%, that is, they were used by the Tiwanaku. “Two of them are bottles what served to hold chicha and the little plate is called a basin; it is not a lid, it is a receptacle, possibly for food,” explained the specialist who, also, is a member of the Archaeology Society of La Paz.

Traffic

This phenomenon is repeated in other archaeological locations in the country, according to the experts interviewed. For example, at the ruins of Samaipata in the Department of Santa Crus, where there exists the remains of the ancient Mojocoya and Inca cultures. Here one encounters the so called “Cerro de Cántaros” [Hill of Jars…or Mound of Vessels], where campesiños find ancient pieces––especially ceramic vessels––to sell to visitors (read the supporting piece on page 6).

The absence of a Patrimony Law to preserve and care for historical objects in on the table for discussion and the Ministry of culture is preparing a project on this topic. Moreover, due to the buyers complaint in which Limachi offered his three relics, La Razón went to Tiwanaku and nearby communities such at Lukurmata and Huacullani, where it was confirmed that there were inhabitants that not only offered for sale alleged vessels that date to the epoch of the City of the Sun, but also weapons that appeared to be pre-Colombian.

Near the Tiwanaku museum, in the shops that sell crafts and other souvenirs, you also find arrowheads that were made before the coming of the Spanish. In principal, the sellers avoid the conversation and deny the existance of pieces of this type. But when they develop trust, they show what they are hiding. One of the women displayed two ancient projectile points, one white and one dark. The asking price was 50 Bolivianos.

With images in hand, the archaeologist Sagárnaga––who works in the Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas y Arqueológicas of the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés––offered the following identification of the objects: “One is milky quartz, the other is black obsidian. The bigger is about 2 cm and a bit in length and the other, it probably exceeds a cm. Because of their size, morphology and material the pieces correspond with authentic pre-Hispanic items, which would have mainly been used for hunting”.

Furthermore, the specialist assured that the objects were from the Tiwanaku culture. “We are talking about an age of around 1000 years. However, to conclusively prove their authenticity as pre-Columbian objects we must subject them to laboratory analysis, that can not be done now, but in my opinion I would say they are originals.”

After they left the seller with her two arrowheads, a boy who works by transporting tourists on his bicycle approached the journalist and offer them a piece of a copper topo for 50 USD. The black market in these relics is a booming business in the municipality. “Be it a monolith of two meters or a projectile point of an inch, in both cases we are talking about heritage objects that can not be in private hands let alone be sold.

It is a crime and it is punishable by law”stresses Sagárnaga.

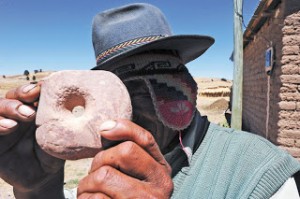

The picture does not change in the town of Lukurmata, two hours away [from Tiwanaku] by car, where there are also archaeological ruins and locals that sell, secretly, fragments found in their chacras, small parcels of land that are cultivated. After asking a campesiño for Tiwanaku crafts, he thought and asked [the reporter] to wait for a minute. He entered into his house of adobe and corrugated metal, and came out with a piece of round lithic of approximately 20 cm in diameter with a hole in the center.

Archaeologist Estévez accompanied the La Razón reporter during the visit, was surprised and guarantees the authenticity of the object and stated it was carved in sandstone, the material in which the Tiwanaku crafted various objects. Back in the city of La Paz, Sagárnaga reviews the image and agrees with his colleague. “It’s a club that, when a wooden handle was placed in the hole, served as blunt weapon. It is relatively easy to manufacture, but I doubt the villager who was selling it knows its morphology so, without a doubt, it is pre-Columbian. ”

But in this trade there exist replicas that are presented as authentic. Estévez complained about the presence campesiños who paint pieces of pottery and who store them under the earth for a month or a year, to gain an ancient look and/or to dig them up during tourist visits or visits of individuals interested in buying relics from the Tiwanaku period. This he verified in Huacullani, two hours away from Tiwanaku.

In the village, a skirted woman [by this the author means she is dressed in Indigenous clothes] offers for sale a vessel and assures that it is pre-Hispanic. “Give me 300 Bolivianos and it is yours, because it is quite old, it is Inca, and it was used by my mother, my grandmother, my grandmother’s mother”, she tries to convince in Aymara. After allowing photos to be taken she reveals that she has other similar objects, but to access them you first have to show her money. In the city of La Paz, Sagárnaga carefully examines the images and concludes that the fragment is not authentic. “The pitcher from Huacullani has a common morphology which reoccurs during various centuries. It could be 500 years or it could be a week old. I think it is contemporary or, at most, colonial”.

And the findings do not stop there. A few meters away from the Tiwanaku town hall, in a normal local provisions store, an old woman offers an alleged “Inca mask” that, according to her, she rarely shows to people. The ceramic piece is wrapped in a black bag and is hidden among beer and Coca-Cola bottles and other products. “I have others which are in my room, but this one is worth US $150.” In reviewing the photos, Sagárnaga concludes that “it is an imitation, seemingly of the Moche culture”.

The main archaeological site is visited daily by at least 200 people, a number that triples on the weekends. [The village of] Tiwanaku lives on tourism and even during the feast day of the town, which is held every September 14, the Gateway of the Sun adorns the banners of the people. On that day, a La Razón reporter traveled to the site to notify the Mayor Marcelino Copaña that one of the empoyees of the museum sells relics.

But Copaña was annoyed when asked about the presence of a “black market” in historical pieces in his municipality. “I don’t think so. That’s a lie, that is false, that we don’t believe. The press has always said those things, but that’s no good. I want the press to tell the truth. Let’s see! Who is that person? (who sells) No! … Lies! It does not exist. That is prohibited, that is prohibited… “.

A little calmer, he adds: “It is not possible to sell anything. Nobody can sell anything, brother, nobody… “. But there is another reality is when you ask villagers for ancient objects. And even though an old legend states that those who move them [archaeological objects] will grow hopelessly ill, locals believe that they are immune to the sickness.

“Me, I do not worry because I’m from Tiwanaku,” says one woman after showing the alleged relic found on her chacra.

El Cerro de los Cántaros [The Mound of Vessels] is another site where one finds pieces

Approximately 30 km from the ruins of the Fuerte de Samaipata, in the province of Florida of the department of Santa Cruz, is the location of the Cerro de los Cántaros, where it is common to find pre-Columbian pieces.

Nestled in a areas of much vegetation and almost inaccessible, the site is named from the many years in which have been found fragments of the Inca, Mojocollas, Omereques, Chané, and Guaraní cultures. “You can find jugs, plates, cups, and other types of ceramic utensils as well as axeheads, bone samples, and lithic (stone) pieces”, explains Richard Alcánzar, an archaeologist who has lived here for 12 years, to the La Razón reporter.

This area is near Floripondio, El Filo, El Toro, the hill La Patria and Las Rueditas, locations of great value to pre-Hispanic archaeology and, for this reason, it is not strange to hear that there are traffickers that are provided these valuable fragments by the huaqueros or excavators who are engaged in finding these artifacts to sell.

However, Alcánzar indicates that the locals have gained an awareness and thus do not encourage this illegal business. “Here there is not much trafficking. The sites are protected and if the villagers find archaeological pieces, they first go through the museum, or they tell us so we can go to the area [where the items were found]” and, afterward, verification is done through laboratory analysis and subsequent cataloging. However, other sources claim, as occurred in the town od Tiwanaku and in nearby communities, there are campesiños that offer tourists the relics discovered in the Cerro de los Cántaros.

Only 40% of the archaeological area of Samaipata and its surroundings have been explored, according to this scholar. “At the moment, we have 357 pieces found in all of the upper middle area, the valleys and those around Mairana”. In recent years, there has been an influx of outsiders coming to the solstice of 21 of June, and with them, there also has been an increase in the desire of those visitors to take away a “momento” of Samaipata, which has caused an increase in traders in archaeological remains, states informants interviewed by the La Razón reporter.

In 1998, the site was declared Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. It is the second most important archaeological space in the country, after Tiwanaku: it is a ceremonial center of the Inca culture whose name in Quechua means “high resting place”. Here there is a sculpted rock that is 250 m long and 60 m high, which was converted into the largest petroglyph in the world, with zoomorphic figures, serpents, and pumas.

The Monoliths of Tiwanaku have Spirits

My son was sick, the doctor said that he was fine and the yatiri said that it was katja, one woman complained; a concern that allowed me to record the past and give an opinion for the future.

They say that when the archaeological ruins of Tiwanaku were not yet restored, a trail ran around them; at that time the first vertical monolith was called by the name “The Frier”. One night, a campesiño of the village was inebriated on a bottle of alcohol after having played football and celebrated the victory. On the path he ran headfirst into that vertical stela of stone. As if in a dream, he heard “Sir, Sir arise, walk to your house, for here is the path and thank you for your trago [grain alcohol]. The following morning he woke up in his house and, not finding his sporting equipment, he asked his wife about it. Her response was categorical about the absurdity of his questions. He decided to retrace his steps and encountered his lost items at the foot of the monolith as well as his broken bottle. Since this, in his dreams, every time he hears: And thank you for the trago! The persistance of these words caused him to seek the services of a yatiri.

On another occasion, Don Lucas Choque, a yatiri, recounted that, when the ruins were beginning to be restored and were not yet fenced, a boy started playing ball with the Gateway of the Sun, as if it was a goal. After days of satisfaction, his punishments were revealed. First one foot crumpled in, then the other, then his arms, until the youngster was almost made into a ball. His parents started with the running about, the interrogations and the investigations, they flew to the house of the amauta, until finally one of the yatiris correctly diagnosed, thanks to coca [leaf divination], the cause and could provide remedy for the case.

Andean wisdom teaches that seemingly inert elements also have spirit. The monoliths are not sculptures made for an aesthetic desire, they have powers. In them live ancestral spirits, and therefore Catholics commonly exorcised them and removed them as idolatries. Be it traditional knowledge or simply witchcraft, today the majority believe that the wak’as are superstitions and trickery. Even prejudices and colonialism rule over many people.